Hackers are constantly scanning the internet for exploitable sites, which is why even small, new sites should be fully patched and protected. At the same time, it is not feasible to scan the whole internet with 330+ million domains and billions of web pages. Even Google can’t do it, but hackers are always getting better at reconnaissance.

Despite these limitations, scanning just 1% of the internet allows attackers to discover thousands of vulnerable sites. There are targeted scans that compile lists of websites with specific software components; for example, Magento sites or sites with a certain WordPress plugin. There are also campaigns that do broader scans of every known domain, probing for certain CMS, plugins, or even backdoors.

When attackers find a vulnerable site, they could attack it right away. On the other hand, this scanning process helps them compile specialized datasets for faster subsequent scans – when they are only interested in sites with certain software installed.

So how broad can these scans get? We can get an idea by using a script that hackers install on compromised sites in order to scan for other sites that have publicly accessible Adminer database management scripts.

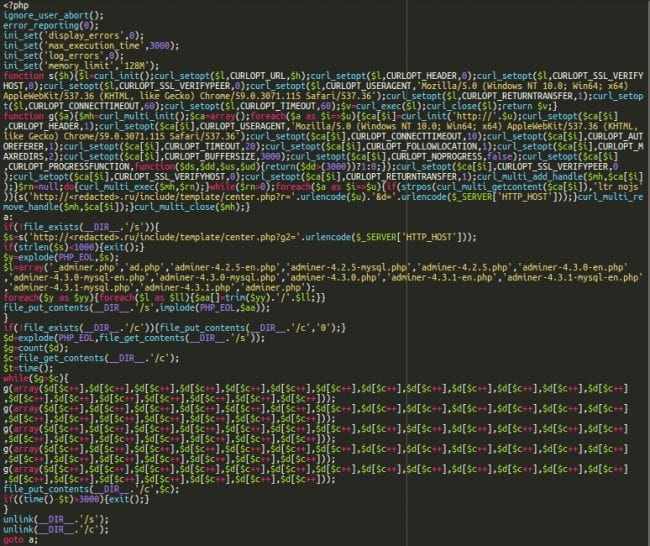

Malicious Scanner Script

We found this script in the at.php file on a site we cleaned.

At first glance, you notice a curl request to a hacked Russian website, along with a list of 14 typical filenames of the adminer script:

- _adminer.php

- ad.php

- adminer-4.2.5-en.php

- adminer-4.2.5-mysql.php

- adminer-4.2.5.php

- adminer-4.3.0-en.php

- adminer-4.3.0-mysql-en.php

- adminer-4.3.0-mysql.php

- adminer-4.3.0.php

- adminer-4.3.1-en.php

- adminer-4.3.1-mysql-en.php

- adminer-4.3.1-mysql.php

- adminer-4.3.1.php

- Adminer.php

So, what exactly is this script doing?

Batches of Domain Names

When we made a curl request to that Russian site, it returned a list of 10,000 domain names.

Except for the alphabetical order of the list, there was no apparent pattern in the way the list was compiled. The sites used all kinds of CMSs that were hosted on different servers.

When we made another request to that URL, it returned a new list of 10,000 domain names. Again, the list was alphabetically sorted – this time, the new list began where the first one left off.

The same happened on each subsequent request.

Estimating Scan Coverage

This way, request by request, this single script can receive a significant number of domain names. Let’s estimate this number.

A typical batch of 10 thousand domains consists of domains that begin with the same letter. The difference between #1 and #10,000 might only appear in the 4th letter (e.g. #1. brucksclub.com … #10,000. brunermotorsblog.com).

For less common combinations, the difference might happen at the second letter (e.g. 1. bklynr.com … 10,000. bladerollermovie.com).

Overall, the script returned over 300,000 domains that began with letter “b”.

According to Wikipedia, “b” is the first letter of around 4.4% of English words – which makes it quite average in an alphabet of 26 letters. If we assume similar frequency for domain names (which don’t have to be English words – or words at all) and ignore domains that begin with digits or with non-ASCII letters, we come to ~7,5 million domains (or ~2,5% of all live domains) as the lowest estimation for the dataset that this attack tries to scan.

Top Level Domains in List

The distribution of the TLDs in that list is not even either. While there are over 200 different TLD on the list, only five of them have shares bigger than 1%.

Just ten of them represent ~97% of the whole list:

- .com (68%)

- .ru (11%)

- .net (8%)

- .org (6%)

- .info (2%)

- .biz (0.6%)

- .mobi (0.5%)

- .me (0.4%)

- .ua (0.3%)

- .de (0.3%)

This list doesn’t match the list of the ten largest TLDs, where .cn is #2 (compared to #48 with 0.001%) and .uk is #5 (compared to #13 with ~0.1%). This probably has something to do with the methodology of how the list was compiled. We suspect that a list of .ru and .ua domains was compiled separately and merged with the global list.

How Does the Scanner Work?

Now let’s see how these large lists of domains are being processed. First of all, we know that the scanner script requests them in chunks of 10,000 domains. That’s quite a big number when you need to make requests to external websites.

As you might recall, for each domain the script needs to probe 14 adminer filenames. This means there are 140,000 requests per batch (or around 100 million requests per campaign.). Of course, you can’t expect a script to complete such a large task in one go.

To work around this, the scanner uses the following approach:

- It saves the list of 140,000 URLs in the “s” file and the current position in that list in the “c” file.

- The script reads URL from position “c” and then makes requests for up to 3,000 seconds (50 minutes). To do it, they have the following setting:

ini_set('max_execution_time',3000);… and this condition:

if((time()-$t)>3000){ exit(); } - To speed things up, the script makes 20 asynchronous requests at once using the “curl_multi_…” function, instead of regular curl.

- Once a batch of 20 requests is complete, the script makes another 20 requests and repeats this routine until the execution time runs out.

- Every 100 requests, a new position in the list is saved in the “c” file so that next time when the attackers activate the script it will start where it left off.

The next question is, what happens when this scanner finds a publicly accessible Adminer script?

Sites With Adminer

The script reports back with any URL that has found an Adminer script. This is stored by the same script that provides batches of domains for scanning, but this time it uses the “r” parameter to specify that the URL contains one of the 14 adminer file names.

What are attackers doing with this list?

Database Access From Local IPs

Some malware campaigns require access to the database. Many webmasters still remember the massive attacks of 2014, where one vulnerability in a popular WordPress plugin allowed anyone to view contents of the wp-config.php file – a highly sensitive file as it contains database credentials. Attackers can compromise the database and add malicious admin users, create spam posts, inject content into existing posts, etc.

To do it, attackers need to have access to the database – but many hosting providers block access to database servers from external IPs. So in order to use the stolen database credentials and hack a site, the attacker has to be able to run their scripts on that server. But to run scripts there, they need to hack the site first. However – if it’s a shared server and the hacker already has access just one site on it – they can use that one site to access the database for any other neighbor sites (given they have their credentials). This is why hackers aim to have at least one site under their control per server.

This is not always possible, so publicly accessible Adminer scripts work as Plan B – giving them access to the database server from the host’s own IP addresses.

Brute Force

Hackers don’t have to rely solely on vulnerabilities to reveal database credentials. Sometimes guessing is enough.

Private servers and VPS (virtual private servers) are quite popular. Their owners usually install all software themselves, and as with everything else, some server admins simply don’t follow best security practices. They might forget to change MySQL root password (which is empty by default) after the installation – or change it to a common dictionary word or character combination like “12345”.

It’s quite common for amateur administrators to use scripts with a GUI, like phpMyAdmin or Adminer, to work with the database, and then forget to remove the scripts when finished.

If attackers find a publicly available database management script on such a server, they might simply try to guess the MySQL root password using brute force tactics.

Load Local Data

There is one more attack vector. You don’t have to rely on weak passwords or the presence of vulnerable third-party software to read credentials from configuration files.

As my colleague, John Castro pointed out, access to the Adminer script may be enough.

Because of the way MySQL works, an attacker may use the “LOAD DATA LOCAL INFILE” query to read contents of any readable files on the server where the Adminer script works.

All they need to do is connect to their own remote server and choose a filename to read, for example, /etc/passwd or configuration files of any site on that server (there are quite a few ways to figure out their absolute paths).

Conclusion

In this article, we showed how hackers use compromised sites in their distributed scans of millions of websites and how relatively harmless, legitimate tools left on the site can compromise the security of the whole server.

To minimize the risks, you should do the following:

- Don’t expect hackers will avoid your site because it is small, new, or uses an obscure CMS. Sooner or later, every site will be scanned by hackers. This post demonstrates that.

- Keep every piece of software up to date. Don’t let hackers find old vulnerable software on your site. You can also use a website firewall that will virtually patch your site.

- Remove temporary scripts after use. If you use scripts for site maintenance (i.e. database management, uploads, search & replace, installations, backups, etc.), make sure you:

- Remove them immediately after finishing the task.

- Restrict access to certain IPs or password protect them (P.S. – the login screen in the Adminer is not a protection of the Adminer script itself)

- If you share a server with other users, act as if your neighbor’s site was compromised. Make sure all files with passwords (e.g. CMS configuration files like wp-config.php or configuration.php) cannot be read from other user accounts, even if they figure out absolute paths of your files. Setting permissions of such important files to 400 (read-only to the owner, nothing to anyone else) is a good idea.

- Strong passwords are mandatory. Always. Especially if you install everything (including the database) yourself. Don’t forget to change default root/admin credentials as the very first step after software installation!

If you need help securing your website and learning best practices for website security, subscribe via email to receive our newsletters, educational content, and/or blog post updates.