Sometimes just a few lines of access logs can tell a whole story…

Many ongoing attacks against WordPress and Joomla sites use a collection of known vulnerabilities in many different plugins, themes and components. This helps hackers maximize the number of sites they can compromise.

Google Dorks

Do you ever think about how hackers find vulnerable websites? Probably the most common way to do it is using “Google Dorks” – special Google queries that use search operators to return sites that use specific software. For example, this inurl operator will help find [improperly configured] WordPress sites: [inurl:”wp-content” “index of”]

Almost every published exploit has its own dork that helps to find vulnerable sites.

Hackers just need to enter search queries and then parse search results. Sounds easy? Not really. There are quite a few obstacles.

Obstacles to Automated Searches for Vulnerable Sites

- Even if your search returned millions of web pages, you can’t get more than the first 1,000 of them from Google.

- Out of those 1,000, not all sites are vulnerable. Some use a patched version, some use a website firewall or a different means of protection that will make the attack fail, or Google has outdated information about the site that might have already removed the vulnerable software. All in all, hackers may expect that less than 20% of the search results will be really vulnerable (It may be more for new zero-day attacks and less for old and already patched vulnerabilities).

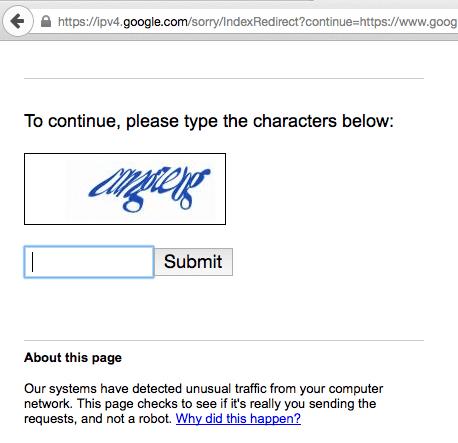

- To compile a big enough list of vulnerable sites, hackers either need to use multiple dork modifications for one exploit, or use multiple dorks for multiple exploits. Both methods assume a significant number of requests to Google search engine. However, as you might know, Google prohibits automated requests. They block IP addresses that submit many requests in a relatively short time. Even human visitors see this CAPTCHA from time to time.

So how do hackers overcome these obstacles?

Enter Access Logs

A few days ago my colleague Rodrigo Escobar checked access logs of one compromised site and shared a very short excerpt with me. Here are the three lines of logs that tell the whole story about how hackers scan the web for vulnerable sites:

5.157.84.31 - - [01/Oct/2015:13:07:39 -0600] "GET /includes/freesans.fr.php?____pgfa=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dwp-content+revslider+site%3Amobi&num=100&start=600 HTTP/1.1" 302 2920 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:21.0) Gecko/20130401 Firefox/21.0"

5.157.84.31 - - [01/Oct/2015:13:08:33 -0600] "GET /includes/freesans.fr.php?____pgfa=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dcom_adsmanager+%2Blogo+site%3Adj&num=100&start=300 HTTP/1.1" 302 2916 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:23.0) Gecko/20130406 Firefox/23.0"

5.157.84.31 - - [01/Oct/2015:13:08:33 -0600] "GET /includes/freesans.fr.php?____pgfa=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dwp-content+%2Brevslider+site%3Amobi&num=100&start=500 HTTP/1.1" 302 2928 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; Win64; x64; rv:23.0) Gecko/20131011 Firefox/23.0"

If you are not fluent in the language of web server access logs, I’ll translate the story for you.

PHP Proxy

All three lines request the “includes/freesans.fr.php” file, which appeared to be an uploaded copy of the open source PHPProxy script. The proxy provides you with a web interface to open web pages from the server’s IP, instead of your local IP address. It’s normally used to bypass country and other IP-based restrictions.

Requests to Google

In our case, the proxy is being called with the following parameters:

?____pgfa=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dwp-content+revslider+site%3Amobi&num=100&start=600

These are the URLs someone tries to open via the proxy. As you can see, they are URLs of Google search results pages.

Dorks

Our three lines of logs correspond to the following three queries:

- [wp-content revslider site:mobi]

- [com_adsmanager +logo site:dj]

- [wp-content +revslider site:mobi]

The first and the third queries look for WordPress sites with the Slider Revolution (revslider) plugin – vulnerabilities in revslider were responsible for a good number of the WordPress hacks we saw last year. Even one year later we see hackers exploiting the vulnerabilities in sites that still use old versions of this extremely popular premium plugin.

The second query looks for Joomla sites with the AdsManager extensions, some versions of which have an arbitrary file upload vulnerability.

Site: Trick

You might have noticed that the Google queries contained the site:mobi and the site:dj operators, which limit search results to websites on .mobi and .dj top level domains. Does it mean that hackers only want to attack WordPress .mobi blogs and Joomla .dj sites? Of course, not!

Hackers use the site: operator only to bypass the Google’s 1,000 results per query limitation. If they find 1,000 vulnerable .mobi sites, 1,000 vulnerable .com sites, 1,000 vulnerable .org sites. 1,000 vulnerable .net sites, and so on for every possible TLD, they’ll get far far more results than a mere one thousand that they could expect searching just for any WordPress site with the revslider plugin.

Distributed Search

The only downside of this trick is it requires more requests to Google which maximizes risks of getting blocked for automated queries. To work around this, hackers use these two methods:

- The &num=100 parameter that increases number of search results to 100 per page, which effectively decreases number of required requests by 10.

- The distributed system of proxies on compromised sites.

We can always tell that hackers don’t care about the sites they break into. They do it only to take advantage of the sites’ resources – be it visitors, server space, bandwidth, CPU, etc. In this case, the resource they need is the unique server IP along with the ability to install and run the PHP Proxy script.

So they have multiple hacked sites on servers with unique IP addresses where they installed the proxy script. To get results from as many Google queries as they want in a relatively short time, they need to make requests via the distributed network of their proxies rather than directly to Google.

This explains why we only see 3 such requests to the proxy script in the logs and why they requested search results in the middle of the result set (e.g. &start=300 or &start=600). Other search requests went to similar proxy scripts on other hacked sites.

Different User Agents

To make the search requests look even less suspicious to Google, hackers change the User Agent headers of each requests. This makes it look different as people share the same IP address (this may be a company behind a corporate firewall or users of an ISP with a dynamic pool of IP addresses).

Indeed, if you take a look at the logs the User Agent look the same at the first glance (Firefox on Windows 7), but if you look more carefully, you’ll notice that versions of Firefox vary:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:21.0) Gecko/20130401 Firefox/21.0

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:23.0) Gecko/20130406 Firefox/23.0

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; Win64; x64; rv:23.0) Gecko/20131011 Firefox/23.0

This resembles a corporate environment were most people use computers with similar configurations (with insignificant variations).

Conclusion

This was a story told by 3 lines of web server access logs. It helped us demonstrate

- Why hackers no longer focus on just one vulnerability and try to exploit multiple different security holes

- Why it is important to update and patch every single element of your site software

- How hackers find thousands of potentially vulnerable sites in a short time

- How they use compromised sites to find their next potential victims

- Why your server IP address is a valuable resource for hackers

Help the Internet — keep your site secure. Don’t let hackers use it to hack even more sites.

We know that it’s hard to keep track of all the newly discovered vulnerabilities in every CMS, theme and plugin, and update them in a timely manner, let alone the zero-day vulnerabilities that don’t even have any patches. Don’t worry! We have you covered!

Our website firewall protects websites by blocking requests that try to exploit both known and even unknown security holes so that they don’t reach your site and can’t do them harm, even if you still use some vulnerable software (it’s still a very good idea to update everything ASAP). Here you can learn more about how it blocks all vulnerability exploits.

5 comments

Great article Denis. Thanks for the detailed explanation. keep up the good job.

Thanks Denis.

And yes, Sucuri WAF Is doing a nice job for a few of my clients I’ve referred to the service. The world is a better place with you guys in it.

Thank you. One of the things I’m seeing a lot of is brute-force attacks where the IP addresses are associated with a wide range of countries but are clearly directed from the same source. For example, right now in the log I am looking at a series of brute-force login attempts against a single username from ip addresses mapped to the following countries:

Sweden

Italy

Spain

India

Poland

Antigua

Serbia

Bengladesh

I’m guessing that your article is the reason why.

Fascinating and interesting. Would never have thought of using a site to query Google to get over the ‘too many requests from 1 IP’

I was struggling with this captcha. In general, it depends how much one wants to search and how quick. I had a small URL scraping for archival purposes, so I had much time finding both site:something.tld and “something.tld” -site:something.tld (then going along URLs and scraping from them).

Now the captcha. If someone wants to trigger it, he should mess extensively with UA. If much UAs are pushed from single IP and with some bad (read: small) timing, captcha will trigger. Many small ISPs, who have 500+ computers behind a router (yes, one router) have this problem.

In example, attackers want to acquire as much as possible as fast as possible. I found that if it’s not the case, the best way is to “play safe”, simulating user actions. Perl, mechanizing existing Firefox, 1-2 seconds delays (randomly changing), 2 threads with two different UAs. No captcha at all.

And one more interesting thing: The way with mechanizing FF and Google with Perl may be used to confuse “information bubble” profiling filters and get an interesting results from searches.

Comments are closed.