Ever had a perfectly “safe” page or file turn into an attack vector out of nowhere? That can happen when browsers start guessing what your content is instead of listening to your server. Browsers sometimes try to figure out what kind of file they’re dealing with if the server doesn’t provide the Content-Type header or provides the wrong one, a process known as “content sniffing.” While this can be helpful, content sniffing is a security risk if an attacker can mess with the content.

A lot of developers focus on checking user input and making sure users are who they say they are, but if your responses aren’t clearly labeled with a type, the browser’s guesswork can actually weaken those security measures. Security headers like X-Content-Type-Options and Content-Security-Policy are your tools for telling the browser to stop guessing. Using them helps protect your site from various attacks and common mistakes.

Below, we’ll dive into what these headers are, why they matter, how to use them, and what to watch out for.

Understanding security headers

What are security headers?

HTTP security response headers are specifically designed to control how a browser behaves in ways that boost security. Instead of changing your application’s code, you set these headers at the web server, reverse proxy, or application level, and the browser does the heavy lifting of enforcing the rules for you.

Think of security headers as being like standard headers such as Content-Type and Cache-Control, but their main job is to shrink the potential area an attacker can target. They help by preventing content sniffing, limiting which domains can load scripts, forcing the use of HTTPS, managing content framing, and much more.

Some of the most important HTTP security headers include:

X-Content-Type-Options– Tells the browser not to guess content types.Content-Security-Policy– Defines which resources are allowed to load and execute.Strict-Transport-Security– Forces browsers to use HTTPS.X-Frame-Options/frame-ancestors– Controls framing and clickjacking risks.

Because they’re delivered with every response, these headers travel with your pages and assets, reinforcing security in the user’s browser even if the underlying application code hasn’t changed. You can think of them as a declarative security layer, where you declare the rules in headers, and modern browsers do the enforcement work for you.

If you want to explore more about HTTP headers and their behavior, MDN Web Docs and OWASP are solid resources to get familiar with.

Importance of using security headers in web applications

The complexity of modern applications means there are many places where things can go wrong, and attackers know it. Security headers give you a simple way to reduce risk.

- Defense in Depth: They provide an extra layer of security that can prevent vulnerabilities from becoming exploitable (e.g., by preventing content sniffing or blocking inline scripts), even if application-level validation or sanitization has a flaw.

- Consistent Website Security: When configured at the server or reverse proxy level, security headers enforce the same policy across all routes and subdomains, which is significant for large or older codebases with legacy endpoints.

- Low-Friction Deployment: Updating a config file or WAF rule is usually faster than refactoring an application, so it’s both a quick win and helps achieve long-term hardening.

- Web Security Best Practices: Failing to implement them leaves obvious gaps that security scanners, compliance frameworks, browser tools, and attackers look for.

Implementing key security headers to prevent content sniffing

X-Content-Type-Options: Preventing MIME sniffing

The star of content sniffing protection is the X-Content-Type-Options header. In practice, you’ll almost always use it with a single value:

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniffThis simple header tells browsers: “Don’t sniff. Only trust the declared Content-Type.” If a response is labeled as text/css, the browser will treat it as CSS, even if the content looks like HTML or something else. If a file is served as text/plain, it won’t be executed as JavaScript just because it contains script-like text.

Without nosniff, an attacker who can influence file uploads or certain outputs might try to smuggle executable code into a file the server thinks is harmless. If the browser decides to sniff and reinterpret that file as HTML or JS, the attacker wins. With X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff, that line of attack gets cut off, as the browser is forced to obey the MIME type you sent.

To make it work well:

- Always set accurate

Content-Typeheaders (for example,text/html,text/css,application/javascript,image/png). - Enable

nosniffglobally at your web server, application framework, or WAF layer.

Examples:

Apache (in a config or .htaccess):

Header set X-Content-Type-Options "nosniff"Nginx:

add_header X-Content-Type-Options "nosniff" always;Once in place, the header is pretty much just “set it and forget it.” It doesn’t typically break legitimate functionality when your Content-Type values are correct, and it reduces the risk of browser guessing turning a minor issue into a major vulnerability.

If you do anything at all to address content sniffing, start with X-Content-Type-Options. It’s one of the highest-value, lowest-effort defenses you can add.

Content-Security-Policy: Control resources on your site

Content-Security-Policy (CSP) is a more advanced way to lock down what happens in the browser. While X-Content-Type-Options focuses on how content is interpreted, CSP controls which content is allowed to load and execute in the first place.

At its core, CSP is a whitelist. You define which sources are allowed for scripts, styles, images, fonts, frames, and more. For example:

Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.example; object-src 'none';This policy says:

- By default, only load resources from the same origin (

'self'). - Allow scripts from your own site and a specific trusted CDN.

- Forbid plugins/embedded objects (

object-src 'none').

How does this help with content sniffing and related attacks? If an attacker somehow injects a malicious <script> tag or a reference to a hostile external script, CSP will block the request unless it matches the allowed sources. If a file is misinterpreted due to a missing content type, CSP still limits what can be executed or loaded.

CSP also plays a major role in mitigating XSS. By disallowing inline scripts (and avoiding directives like 'unsafe-inline' wherever possible), you dramatically shrink the attack surface. Even if untrusted data appears in your page, the browser won’t execute it as JavaScript unless it complies with your CSP rules.

Implementation tips:

- Start with Report-Only mode using the

Content-Security-Policy-Report-Onlyheader, so you can see what would break before enforcing it. - Gradually tighten your policy, focusing first on high-risk areas like scripts and iframes.

- Avoid overly permissive patterns (

*,'unsafe-inline','unsafe-eval') except as a temporary step.

CSP takes more planning than X-Content-Type-Options, but once deployed, it’s a strong, flexible safety net for your entire front end.

Best practices for configuring security headers

Testing and validating your security headers

After you configure headers like X-Content-Type-Options and Content-Security-Policy, don’t assume they’re perfect. Test them.

Use your browser to confirm that each response includes the headers you expect.

In Chrome:

DevTools > Network > select a request > Headers tab > Response Headers

Make sure you’re seeing correct names, correct values, and that they’re applied to all relevant routes (HTML pages, APIs, assets, and so on).

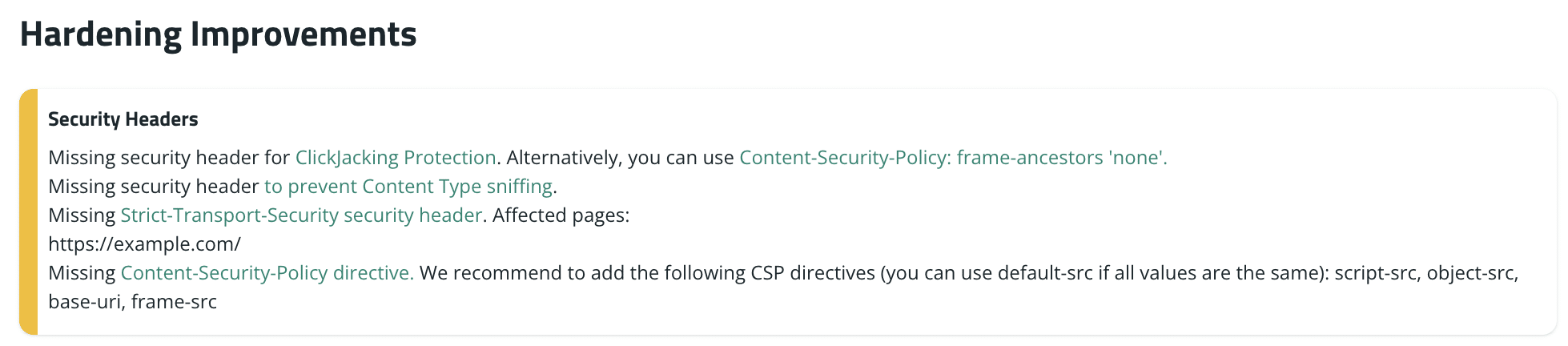

Then use a scanner like SiteCheck to get an independent view of your security posture. These tools will highlight missing or misconfigured headers and inform you of how well your site is aligned with current best practices.

Pay attention to the console warnings and any report-uri / report-to endpoints you’ve configured. These reports will show you which resources would be blocked under your policy, helping you refine it without breaking legitimate functionality.

Lastly, involve dev and QA in the process so compatibility issues with things like third-party scripts are caught early.

Regularly updating security configurations

Your application changes over time, and your security posture should evolve with it. Every time you add a new third-party script, integrate a new service, or change hosting infrastructure, review your security headers. Does CSP still reflect the actual resources your site uses? Are you still enforcing nosniff on all endpoints, including new ones?

Make header audits part of your regular security checklist. Track your policies in version control so you can see what changed and why, and roll back quickly if you introduce a misconfiguration. Also keep an eye on browser security features and recommendations. New directives and best practices appear over time, and updating your headers is often one of the fastest ways to take advantage of them.

Common mistakes to avoid when implementing security headers

Security headers are powerful, but also easy to get wrong. Here are some common mistakes to avoid:

- Failing to set X-Content-Type-Options globally: Not setting the header at all, or only applying it to HTML responses leaves API responses, file downloads, and asset endpoints vulnerable.

- Using overly permissive CSP rules: Directives like

script-src * 'unsafe-inline' 'unsafe-eval'disable the protection CSP is designed to provide. - Forgetting about non-HTML responses: JSON APIs, images, downloadable files, and error pages must also be served with proper

Content-Typeand security headers, as inconsistencies create gaps for attackers. - Overly strict policies that break the site: A CSP that blocks necessary resources can cause visible failures. It’s important to start with Report-Only mode, review logs, and roll out changes incrementally.

- Configuring headers on the application but not the edge: CDNs, reverse proxies, or load balancers can strip or override headers, so make sure all layers (origin server, CDN, WAF) are aligned.

- Setting security headers once and never revisiting them: New pages, third-party tools, and hosting changes can invalidate old configurations, making the policy either too loose or too restrictive over time.

Know what you’re trying to achieve, test thoroughly, and treat header configuration as a living part of your security strategy.

Final thoughts

Content sniffing sounds harmless, but in practice it can open the door to serious vulnerabilities if you’re not careful. When a browser guesses the type of content instead of trusting the server, attackers get room to maneuver.

Good thing you don’t have to accept that risk. With some well-chosen HTTP security headers, you can tell browsers exactly how to behave. X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff closes off MIME sniffing and keeps content interpretations predictable, while Content-Security-Policy adds a powerful layer of control over what can load and execute on your pages. Together, they give you a solid baseline to protect your users and reduce the exposure to browser-based attacks.

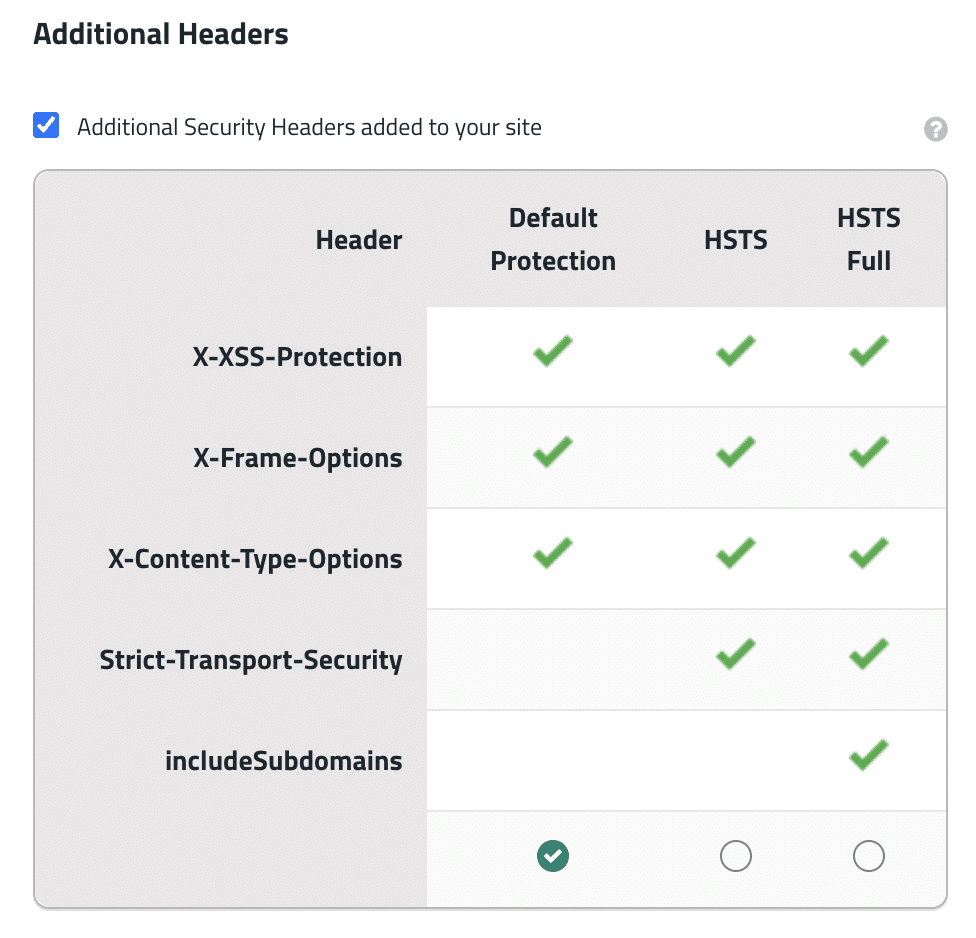

The Sucuri Firewall offers a range of security options that apply uniformly at the edge, ensuring your headers are enforced even if your application or server configuration is inconsistent.

If you haven’t reviewed your security headers lately, now is the time. Start by auditing what your site is currently serving, then consider layering in a firewall solution that enforces these protections consistently and automatically. Combine strong headers, ongoing monitoring, and a WAF tuned to your environment, and you’ll be well ahead of the most common web threats targeting modern sites.