How often do you think about the passwords you’re using? Not only for your website, but also for everything else you do on the internet on a daily basis? Are you re-using any of the same passwords to make it easier to remember them?

We see it all too often: weak passwords used to secure website login for FTP, database, cPanel, and the CMS dashboard. Everyone has their own password policy. It’s very personal and usually based on a set of assumptions about online security. Many users choose policies of efficiency over security. Even the paranoid among us have to confront the truth. Like any defensive measure, best practices in password management can only minimize the level of risk.

Password management is a choice, and a habit. By taking a good look at the risks, users can make informed decisions and put better passwords into practice.

History of the Password

Most password strength meters are too soft. The companies that use them know this, but they don’t want users to leave the registration process due to a restrictive password policy. Modern software can guess many so-called “strong” passwords in minutes, and the most common passwords in milliseconds. As password hacking grew in complexity over time, so did the requirements on passwords.

- In the beginning, there were no restrictions on password length or composition.

- Then, it was decided that a basic eight character password was sufficient. All lowercase? Sure!

- Some time later, a symbol, a number, and a capital letter would increase the strength meter.

- Others argued that longer passwords are stronger than complex ones.

- Then we found out how fast a computer program could use a dictionary… and Wikipedia.

Now, using common words, names, and phrases weakens a password significantly. The number of word lists available is growing all the time, and these lists make it faster and easier to crack passwords that we used to think were strong.

![Common Passwords [Source: http://lorrie.cranor.org]](https://blog.sucuri.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/badpassword.jpg)

How Does a Password Get Hacked?

Computers work incredibly fast, and hackers have access to huge amounts of data to help the computer guess more efficiently. On a typical US keyboard there are 94 possible characters. A brute force attack, in its basic form, attempts to guess every possible combination of these characters, until the hacker gets into the account. This method works quickly if the password is fairly short, but can be exhausting with longer passwords. A dictionary attack is a more efficient way to guess long passwords. This uses the same technique as a brute force attack, but instead of guessing all the character combinations, it tries from a list of common passwords and words from dictionaries and literature. Even at almost fifty characters, including symbols, you can’t use the call of Cthulhu as your password. We’re at a point where even the use of common substitutions, L1K3 TH15, are part of most common word lists.

The Rise of Password Breaches

In addition to all of this, even a strong password isn’t a guarantee. The odds of a password getting leaked, due to a data breach or research initiative, are on the rise. With the sheer number of password breaches that continue to occur, hundreds of millions of potentially active passwords are floating around in cyberspace.

Both bad guys and good guys look at password dumps to research the most common passwords and patterns. This data reveals many common tricks that people use to make passwords memorable and strong at the same time.

Clever methods of making your own passwords become transparent with enough data:

- Pattern-based passwords (qwerty678^&*)

- A capital at the beginning and a number and symbol at the end (Password1!)

- Common substitutions (P@ssw0rd)

- Words associated with the user or website (Username@2014)

Once discovered, someone can design a program to exploit these methods via methods known as Brute Force attacks, and in turn, that program can expand the word lists that are used.

A variety of social tactics can also be used to reveal passwords. By spoofing an email address, attackers can lure users with phishing emails that seem legitimate. Similarly, malware on a computer may attempt to scare users into revealing information. In targeted attacks, hackers will use any personally identifying information they can find (such as your birthday, or your dog’s name) to enhance their attack.

For website protection against these kinds of attacks, we recommend using a web application firewall, like CloudProxy. This stops malicious users from breaking into your site.

Reuse is Never a Good Thing

If you don’t use a strong password generator, then you need to ask yourself this question: When multiple sites that you’ve registered with get hacked, and your handmade passwords can be compared, how hard is it going to be for an attacker to figure out your method? While many people reuse entire passwords, a significant number choose a common base and incorporate the site name, or something else to make it unique. There are two problems with this method:

- This method gives a false sense of security by making you believe it’s a safe password.

- This method makes it easy to guess all of your passwords.

Even reusing part of an old passwords is risky. Changing or adding characters to an old password is dangerous, when we know a computer can modify the original password with billions of iterations per second.

Password reuse does have the virtue of being fast and easy to remember. It’s been suggested that a few passwords can be reused effectively across specific groups of accounts, but the goal with this is to get more people on board with password security in general. For those who are stuck reusing the same password habitually, it is easier to gradually move to a system of password levels. By creating a few strong, memorable passwords, each one can be reused among accounts that require similar levels of security. The key is to never share a password across security levels. For example, use the strongest password for email and banking, a difficult one for social media, and the weakest password for streaming music.

All reuse scenarios have one thing in common: When one account is compromised, it takes much less effort to compromise the same user’s other accounts. There may be pieces of personally identifying information in low-level accounts that attackers might use in a targeted situation. Password reuse levels are there for those who don’t trust a password manager to save generated passwords for all accounts.

Password Tools Make Security Easier

Generating a password is a great way to have unique, random passwords for every account. There are plenty of password generators online and most offer options to increase the length and complexity of each unique password.

If the idea of having one password is appealing, get a password manager. There are plenty of reviews online to help decide which one is right for you, and they generally work the same way. Make one killer Master Password, then let the application record, scramble, and store all online passwords. After logging in to the password manager, it automatically fills in your passwords as you go. This makes it faster and easier to use strong passwords, and it can also stop keyloggers from capturing your password if you were to type it.

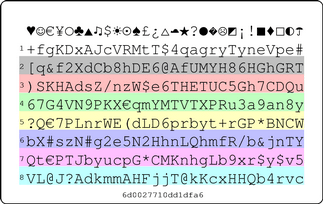

A lot of people still rely on pen and paper. This is dangerous for a few reasons, including loss and theft. One of the better options is to generate a password card. The card is filled with random character combinations. You choose where to start , which direction to go in, and how long it should be. Only you know where your password starts and ends.

Moving Beyond the Standard Password

With all these restrictions, we might question whether a text-based password is strong enough on its own. Plenty of organizations are embracing two-factor authentication. When you enable 2FA, your phone receives an additional code that you need to enter when logging in from a new device.

We mentioned US keyboards, but it’s good to know that some password fields also accept Unicode characters. These are characters like: €, Γ, and λ. You can find more about them here, and we may write more about them in a future post. If you can use them, great. It’s one way to make your password less guessable.

Finally, biometric authentication allows you to use your unique physical characteristics (such as a fingerprints, heartbeat, or retina) to log into a system. Many business laptops and Apple’s Touch ID offer fingerprint scanning already, for those inclined to use them. We may see passwords replaced, or supported by these alternatives in the future.

Let’s Talk About Entropy

Entropy is the word used to describe how random a password is. The more entropy a password has, the stronger and less predictable it is. Using longer passwords increases entropy exponentially. Adding character sets (numbers, symbols, unicode) increases the permutations available for any length of password. If your password, or part of your password exists in a word list, it isn’t random. If your password is based on a pattern or common base, it isn’t random. When password entropy is low, the password is easier to predict.

We still see that many password fields haven’t evolved past the simple eight-character requirement. It doesn’t help that password strength meters can differ greatly from one to the next. It can be frustrating trying to figure out exactly what makes a password “strong” or theoretically unpredictable. All the while, there is talk of quantum computers that aim to be so fast, they could break any encryption with ease. So, maybe it’s time to download Google Authenticator and get used to 2FA.

In Conclusion

It’s difficult to imagine a future-proof password. Making passwords unique, complex, and longer is a start, all of which are easily accomplished with a decent password manager. Perhaps we’ll see new authentication methods. One thing is certain, as computers evolve in terms of processing speed and storage capacity, requirements on password entropy will need to evolve with it.

What we do know is that password breaches are gaining popularity, and the standard password is not going away. Like anything to do with security, you want to know the risks and put a policy in place that keeps you one step ahead of potential threats. When it comes to your personal accounts and site visitors, protection against brute force and dictionary attacks is an important step to take.

9 comments

Very well covered. Having worked for some large companies in the past, I have seen many pitfalls when it comes to password management. Trying to get people to change is very hard, even when it is for the protection of the data they prize so highly. I have seen passwords using simple number and letter combinations for root access, telnet (yes, telnet) access to corporate VPN’s, and some data not even protected; although considered highly sensitive to the organization and definitely valuable to the outside world.

Pushing the change to longer, stronger and non-so-common substitutions is something many are resistant to. I have seen, in more that one organization, where executive management has refused password policies “because it’s too hard for people to remember”. When offered tools, like two factor, they are rejected due to being another step to accessing their computer or data. Fortunately I have always had an option to control the servers and data management systems, and have used long, strong and two-factor whenever I could. This of course was met with resistance by junior admins or peers, but when discussed and proven with haystack testing methods, they eventually understand and start to make similar changes in their own behaviors.

One of the best companies I had worked with four years ago was also the strongest in my opinion. They operate worldwide and any access to corporate resources required three steps. They used a VPN to access the desktop, as all data was stored on their systems, nothing was local to anyone’s PC. To access the VPN required a logon password no less than eight characters, followed by two-factor authentication (fob or phone), then followed by a four digit pin. This was one of the strongest processes I have ever seen in my career. Considering the work they did, it was well worth it to keep the data in-house and well protected. The beauty of it was it was open-source technology!

As data breaches are very common, although most not reported, I like seeing sites like Sucuri.net providing relevant information and a free service.

I was going to put in some password generators, but a simple search will lead to quite a few tools that can help with this, although most will not remember the generated password. To help remember them, there are quite a few programs you can use, two I recommend are KeePass (http://keepass.info/) and LastPass (https://lastpass.com/f?4665586). Yes I did stick a reference number in there, just visit lastpass.com if you do not wish to give me a free month. Both of these use a single password, like mentioned in the article, to protect all your passwords. Using a single strong password to protect your other randomly generated ones, helps eliminate using the same password on multiple sites. Both programs will generate random passwords, based on criteria you specify, then allow you to save them. Both allow non-US keyboard characters as part of the generation schema. As for usability, KeePass is a bit more work, but allows portability of your data on a thumbdrive; or you can store the encrypted files in the cloud. LastPass is browser integrated and does most work for you, just having to click save after generating. Both are free, although LastPass does require a subscription ($12/year) to use on your mobile device. Regarding the strength of a password, you can try these free sites. Although be wary what you type, nothing is truly secure when transmitted over the web.

How big is your haystack? – https://www.grc.com/haystack.htm

Password test – https://howsecureismypassword.net/

Password strength meter – http://www.passwordmeter.com/

Kaspersky password check – http://blog.kaspersky.com/password-check/

Accept

Thank you for your comment Anthony, you hit the nail on the head. The real challenge is getting people to see security as an essential and valuable part of their character, not as a burden or inconvenience.

Wearing a seat belt and following the road signs may not prevent a car accident, but we all like to pride ourselves on being good drivers. 🙂

Very good post.

Although we’ve seen (we – I mean developers and security people) the same weak, short and predictable passwords in many places, every day. People don’t want to use strong passwords (there’re a lot of reasons, eg. they are hard to remember or in many cases people simply don’t know consequences of password leaking)

You can change password, but you can’t change human nature and laziness 😉

I think I have this exact conversation with at least one client daily. I know you touched on password helpers and I just wanted to share how we implement this in a corporate setting.

We use LastPass Enterprise combined with physical 2FAs (Yubikey Neo’s). We employ IP restrictions on the account and each team member is given an account to which the don’t even know their master password. The master password is extremely long and complex and auto saved to each users machine. Without the Yubikey they cannot access the account. They can’t go home and access the account either because of IP restrictions and because they don’t know the password. Shared passwords within the account are prevented from being coppied or revealed. Managers have access to the account from mobile devices, but only with a pin and NFC 2FA from the Yubikey. If a Yubikey is obtained by a hacker, they would still have to guess that password that no one knows.

This may sound like an overkill or excessively complicated, but it’s not. The last thing we want is a week password generated by a lazy employee to be the Achilles heal of our clients personal and credit card data.

I think that’s brilliant! It only takes one lazy/incompetent/ignorant employee to be the weak link that sends a corporation into hackers delightful world. Seems to me more companies should consider the same approach. The more sensitive the data being handled, the tighter the security belt should get.

Isn’t the ol’ battery-horse-staple type of generator still the best mix of memorability and non-guessability, especially if it’s salted with some random non-alphanumeric characters? http://xkcd(.)com/936/

Ordinary users find most of these methods draconian

For many of them a password manager is too much and they need to be conditioned to accept it

When the user is in a home environment and resistant to password managers and long secure passwords I recommend the following as a first step to help them become comfortable with the idea of unique and unfriendly passwords

1. Explain to them that passwords must be unique but can be easy to type and remember (for the regularly used) if they are simply longer

2. Keep a book

In the home environment this book is safe from the hacker and (unless your are a high profile target) relatively safe from thieves/intruders (those who would break into a home likely wouldn’t look for it or know what to do with it)

Relatives are a concern and the book should be hidden or locked away from all but those who we trust completely

3. Create a separate page for each account (many users already write down their passwords but scribble it all on one page or miss important information and end up in a cycle of resetting the password for their AppleID when they were actually being prompted for their account login to install flash)

4. Create the password using a variation of horsebatterystaple

The variation is – look around, pick unrelated objects, non personal, total of at least 16characters (btw why does microsoft have a maximum password length for Office365?), use simple capitalisation, add a number, add punctuation only if forced

DO NOT reuse words from previous passwords

DO NOT reuse parts of previous passwords

This will generate passwords like ShoeWindowBiscuit7575

(passwords like this, importantly are easier to tap than qwerty678^&*)

5. Write it in the book

6. Get comfortable with this process (getting used to referencing the book for occasionally used passwords and simply remembering through regular use those that are used often)

7. Migrate to a password manager and begin to use auto generation

Go ahead, scroll to the end of this thread, read a couple of the other passwords mentioned and try to remember them

Then try to remember ShoeWindowBiscuit7575 without referring back to my post – I bet you can and so can your resistant friends and family

Thoughts?

Why not just use a password manager? It makes it super-simple and very secure. Why is a password manager too much? Sorry, does not compute. 🙂

Comments are closed.