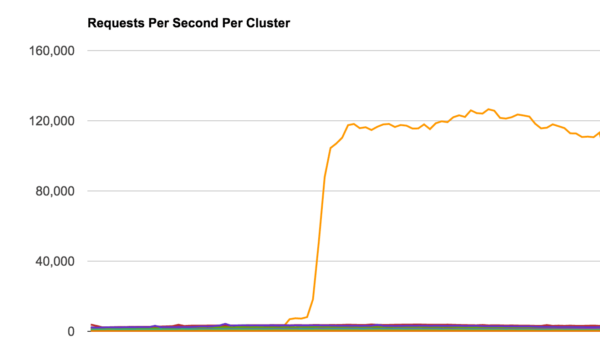

We have been monitoring a large-scale Layer 7 HTTPS flood attack (i.e., application level DDoS) against a customer over the past few weeks. It is being distributed across 47,000 IP addresses and has been pushing over 120,000 HTTPS requests per second (RPS) to the website.

Unlike volumetric attacks that target the network link (measured in bits per second), application-based attacks are designed to target the application and web server resources (measured in requests per second).

This customer came to us after trying to mitigate the DDoS attack using Amazon (AWS), Google (GCE), and other cloud-based auto-scaling solutions. At this scale, most load balancers and VPS cloud instances cannot sustain this level of traffic.

For this website owner, the attack was big enough to disable multiple web servers and quickly exhaust their available bandwidth. This was further exasperated through the use of HTTPS requests, which is more CPU intensive because of the TLS/SSL handshake.

DDoS Botnets

An application-level DDoS attack is not the most interesting aspect of this story.

We recently shared a post on a CCTV-based botnet used to initiate large-scale application-level DDoS attacks against websites. We also shared insights into how unsuspecting WordPress sites can form a malicious botnet to perform DDoS attacks via the XMLRPC feature. In both cases, attackers gain enough computing and networking power to send more requests than victim sites can handle. This forces the victim to add more computing and networking power to fight off attacks, which is highly unrealistic for most website owners.

This website owner tried several options to combat the DDoS attack. They tried the AWS auto-scaling service but reached a point where the cost was too great. They were paying large sums of money as the attack grew. For the attacker, using a botnet means they pay nothing to succeed. The victim has to pay for additional servers and bandwidth, while attackers get it for free using their malicious botnets.

That resource and cost imbalance makes DDoS mitigation tricky for most website owners.

Analyzing the 120K Layer 7 DDoS Attack

If you recall our CCTV-based botnet, the attackers had compromised 25,000 different IoT CCTV devices for their DDoS campaign. They were also generating an excess of 35,000 HTTP RPS against the site. In contrast, the attack we are analyzing today is four times (x4) the size of the CCTV-based attack. How did they achieve this?

In this case, attackers were making use of multiple botnets. They either rent or trade with other attackers distributed across 47,071 + IP addresses. By fingerprinting the IPs, we were able to profile 3 different botnets:

- IoT CCTV Botnet (same as previously disclosed)

- IoT Home Routers Botnet (new)

- Compromised web servers coming from data centers (very common)

This new distribution allowed the attacker to generate a massive number of requests per second without affecting the operation of the infected devices. Under this configuration, the devices would only need to generate a few requests per second – well within their means.

IoT Home Router Botnet

Perhaps the most interesting bit of data for us (being that we’re very familiar with CCTV and compromised web server botnets) was the introduction of the home router botnet. While we have seen routers being used maliciously in the past, we have never seen them used at this scale.

In this case, home routers made up 25% of the IP addresses, resulting in about 11,767 compromised routers. We were able to fingerprint the makeup of the home routers and it came down to eight major router brands being used in the campaign.

Routers being targeted by attackers is nothing new. Over the years there has been a lot of discussion in the community over the inherent risks they introduce to networks, along with other “plug-and-forget” devices (ex. WAPs, modems). Most notably, routers have been used for things like DNS hijacking, distribution of malware, and even vigilante malware (e.g., Linux.Wifatch).

While it has always been a possibility, seeing a DDoS rolled into one large-scale home router botnet was new to us.

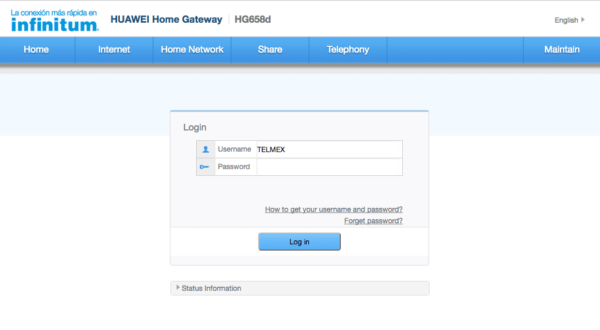

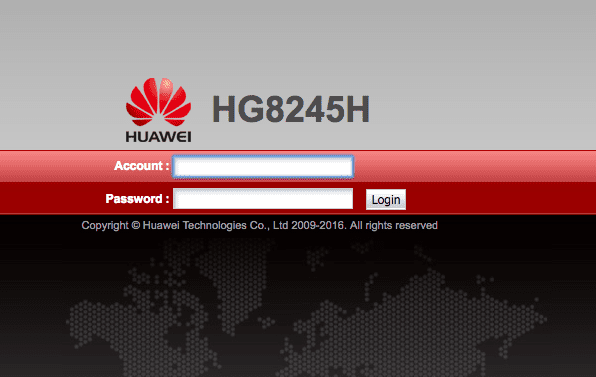

Huawei Routers

The largest number of routers being exploited came from Huawei-based routers. They varied between versions: HG8245H, HG658d, HG531, etc.

We identified at least 6,015 compromised devices (51%). It’s difficult to know exactly how they were exploited, but a good place to start is with the brand’s security advisory page.

RouterOS Devices

Mikro RouterOS was the second most popular router behind this attack with 2,119 devices (18%).

AirOS Routers

Third place goes to AirOS, a Ubiquiti Networks device with 245 home routers.

Others

These were not the only routers being used. The rest were distributed across a number of different providers including NuCom 11N Wireless Routers, Dell SonicWalls, VodaFone, Netgear, and Cisco-IOS routers.

IoT Home Router Botnet Diversity

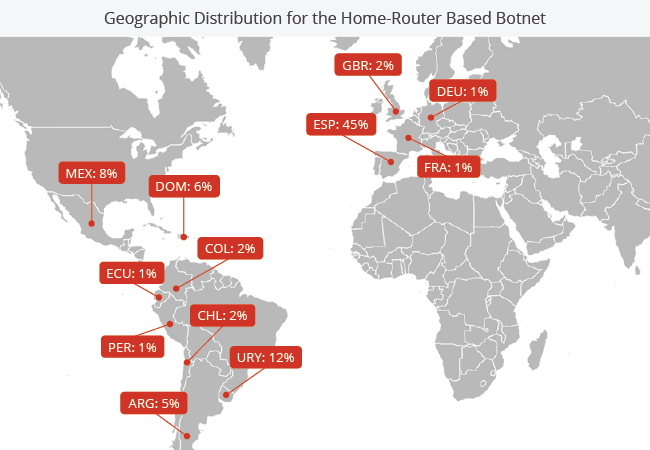

A key requirement for the success of these attacks is diversity. This includes geographic distribution, ASN, ISP, and IP networks. This home router botnet had solid diversity with a heavy focus on Spanish-speaking countries (e.g., Spain, Uruguay, and Mexico). The more diverse the networks are, the harder it is for the victim site to isolate the attack and block one or two networks.

Here is the geographical distribution for the home router botnet:

The attack came from 175 /8 networks and 5,000 /16 distinct networks.

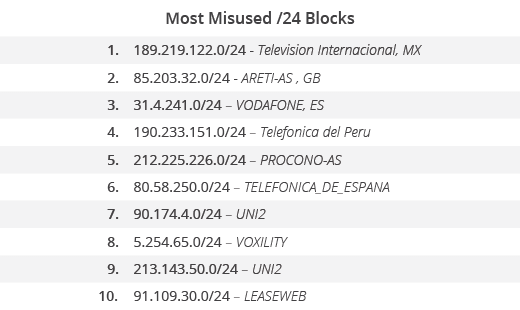

The most misused /24 blocks were:

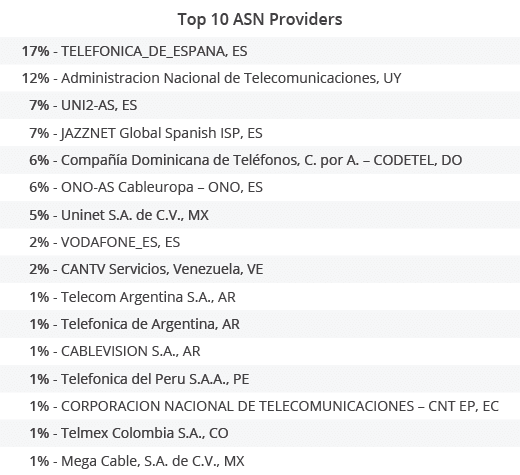

In terms of ASNs, these were the top 10 providers:

IoT Botnets on the Rise

This tale of large-scale attacks distributed across multiple IoT botnets is only scratching the surface of what we can expect in the future. As more devices become part of the IoT ecosystem, the greater the threat becomes. We know that human behavior tends to favor convenience over security when it comes to maintaining their devices.

In conducting our research, we made attempts to identify the attack vectors used in the exploit but fell short due to limited access. We were able to locate a number of public exploits, and many of the devices have not been patched. I would assume that a large number were likely abused through the use of weak or default router passwords.

If you want to check if your router is compromised, F-Secure has a great online scanner that remotely checks for any external issues. While it won’t address all issues, it will look for things like potential DNS-hijacking.

A great resource to help walk you through the process of securing your home router is: http://routersecurity.org/

If your website is experiencing availability issues (meaning it continues to go down or your web servers are being exhausted) you might benefit from leveraging a cloud-based website application firewall that specializes in DDoS attacks.

15 comments

I’m interesting to know what makes these home routers “IoT” devices?

We actually debated internally if we should call them IoT or not, since they are just routers.

We ended up agreeing to IoT because they are part of the multitude of devices people have at their homes and are generally forgotten, unmanaged and unprotected. It includes cameras, watches, routers, etc, etc. That matches the wikipedia terminology:

“The internet of things (IoT) is the network of physical devices, vehicles, buildings and other items—embedded with electronics, software, sensors, actuators, and network connectivity that enable these objects to collect and exchange data.”

thanks!

Hmmm, interesting viewpoint.

I always think of IoT devices as embedded systems that are doing something (collecting data via sensors etc.) and working together in order to achieve specific tasks, whereas a router (or switch or access point etc.) is just an incidental network device that only serves to connect other network devices.

However, much like “cloud”, “IoT” is an overused, vaguely defined marketing term which can be applied to pretty much anything that’s got some form of network connectivity.

For example, is a network connected printer an “IoT” device, or is it just a printer?

In the case of the printer, you send it something from a computer and it prints it, whereas more classic IoT devices (thermostats etc.) generally need a collection of different devices which work together in order to accomplish something.

The printer also takes direct human input (the file to print) and translates it to a physical output, whereas a lot of IoT is normally about M2M communication and human involvement is pretty limited and infrequent (setting a temperature on a thermostat for example).

That’s the same debate we had 🙂

But I agree with you, routers are in a bit of a grey area and can be classified as IoT or not, depending on the view point.

If you update the Firmware on your Ubiquiti device then you wont have this problem. You can’t blame Ubiquiti if the end-user is running 4 year old firmware.

We didn’t blame them. We could blame the owners of these devices, but they are victims as well and likely not technical and unaware they even have to update.

I know some real professional hackers who has worked for me twice in the past

one month. They are very good at hacking anything concerning database,

phone, social media and even credit report fixes. They offers legit services. They

also helps to retrieve accounts that have been taken by hackers. Contact them if

you need such service Alphafasttunnel247@cyberservices.com

How do you know traffic was coming from the routers and not from a compromised device behind the routers? Isn’t NAT mostly undetectable from the outside?

Hi Mark,

Good question. We use passive OS fingerprinting to see what type of stack is connecting to us. That gave away that the connection was actually originating from these devices and not from a desktop hidden behind it.

thanks,

Not to ruin your article or anything but I didn’t use a botnet lol.

How are a bunch of compromised routers, an IoT attack? Where are the lightbulbs?

I am surprised to see Router OS in the list, any idea what version of the Router OS were used in the attack ?

The RouterOS is not vulnerable but the misconfig is the problem .

Your talking about Mikrotik RouterOS? Honestly you shouldn’t have the router’s admin ssh winbox interfaces open to the internet.

Any Draytek Vigor routers in the compromised list?

Comments are closed.