Many are likely getting emails with the following subject header: Large Distributed Brute Force WordPress Attack Underway – 40,000 Attacks Per Minute. Just this week we put out a post entitled: More Than 162,000 WordPress Sites Used for Distributed Denial of Service Attack.

What’s the Big Deal?

Remember life before social media? How quiet and content we seemed to be. How the only place we got our information from was the local news or cable outlet? A phone call, or via email?

Today however, we seem to be inundated with information, raw unfiltered data, and left to our thoughts and perceptions as to what they really mean. Every day there is some new tragedy – a plane goes missing, a child is abducted, a school shooting, the brink of WWW III. Is it that we really live in a time of heightened violence and despair? Or could it be that the only difference between now and then is the insane amount of information at our fingertips?

With this in mind, yes, it’s true, there are ongoing Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) and Brute Force attacks against WordPress sites. In fact it extends far beyond that specific platform, it’s affecting many other platforms like vBulletin, Joomla, and Drupal. The reality is that these attacks have been ongoing for many months now, so much so, that they’ve become part of our daily life and it’s not when they happen that we’re surprised, quite the contrary, when they don’t.

Maybe we get too immune to the issues, maybe we don’t do enough to share and provide feedback. It’s likely attributed to the type and scale of the attacks we see, or the depth of the website landscape we look at. Either way, this post will hopefully get us all comparing apples to apples.

Let’s talk about the biggest issues facing website owners to date in 2014 – Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) and Brute Force attacks.

Denial of Service (DoS) / Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS)

Denial of Service (DoS) attacks and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are the same thing, except for scale.

When you hear someone mention a DoS attack, you can expect the attack to be marginal (Qualifier: obviously marginal is very subjective and many would disagree that any DoS isn’t marginal). In most instances, when you hear someone say DDoS, think grand.

In either case, whether a DoS or DDoS, the attacker is making use of one or more computers. DoS attacks are on the lower end of that spectrum while DDoS attacks are on the higher, very large DDoS attacks can use 100’s if not 1,000’s of systems (often all compromised). In fact, one of those compromised servers might be your own website server, ever think of that? There is also the possibility they leverage pingback features such as the one we shared earlier this week.

The principle of a DoS / DDoS attack is very simple. The idea and intent is to disrupt your service, regardless of what it is. The US-CERT (United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team) provides this description:

In a denial-of-service (DoS) attack, an attacker attempts to prevent legitimate users from accessing information or services. By targeting your computer and its network connection, or the computers and network of the sites you are trying to use, an attacker may be able to prevent you from accessing email, websites, online accounts (banking, etc.), or other services that rely on the affected computer. – US CERT

The proliferation of DoS/DDoS attacks is undoubtedly attributed to the ever-growing DDoS-for-hire service market, a.k.a Booter Service, and the media’s infatuation with the scale of such attacks. Brian Krebs wrote an outstanding article on the new norm when it comes to DDoS attacks – 200 – 500 Gbps(GBPS = Gigabytes Per Second). Now, for those unfamiliar with Gigabytes Per Second – that is a very large amount of data, folks. These are not likely the things you, as everyday website owners will be facing though. What you’re more likely to experience are a much smaller scale, think less than 20 GBPS on average.

Don’t be fooled though, the impact and intent are the same – to disrupt your website’s daily operation.

Why DDoS a Website?

As for the why, here are a list of reasons we have come up with that best help comprehend why someone would do something like this:

- People bored with nothing better to do.

- Political agenda – Malaysian Elections 2013.

- You’ve pissed people off – Brian Krebs – The Researchers Hackers Love to Hate.

- You’re in competition with each other.

Do you fit into any of them? The odds are that everyone reading this most likely does, at least into one category, and that right there folks is the biggest challenge with addressing a problem this large.

Brute Force Attacks

Now, let’s take a moment to shift our focus to brute force attacks.

Brute force attacks, although sharing some similarities with DoS/DDoS attacks, are independent attacks. Their entire focus is completely different from what you would come to expect of DoS / DDoS attacks.

In a brute force attack the objective is to gain access to something.

The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) group provides us a more eloquent description:

A brute force attack can manifest itself in many different ways, but primarily consists in an attacker configuring predetermined values, making requests to a server using those values, and then analyzing the response. For the sake of efficiency, an attacker may use a dictionary attack (with or without mutations) or a traditional brute-force attack (with given classes of characters e.g.: alphanumeric, special, case (in)sensitive). Considering a given method, number of tries, efficiency of the system which conducts the attack, and estimated efficiency of the system which is attacked the attacker is able to calculate approximately how long it will take to submit all chosen predetermined values. – OWASP

Brute Force Attacks and Websites

The explosion of Content Management Systems (CMS) like WordPress, Joomla, Drupal, etc. have made it such that any person looking to quickly establish a virtual presence is now able to do so with little to no effort. From the platforms perspective this is awesome, right? User adoption, market domination, ease of use, happy consumers? Just look at WordPress with over 20% market dominance in the website industry – impressive I know.

Guess who else thinks it’s impressive too? That’s right, the attackers. They realize how the website landscape has changed: it’s no longer combating large organizations with large staff dedicated to security. Instead it’s you – small business owners, bloggers, podcasters, readers, and writers alike. It’s people who have the need to disseminate information easily and freely. Unlike the times of past, this new breed of website owners care more about their content and its distribution than the integrity and security of their website. In fact, if you talk to most website development and design shops you’re likely to get horror stories when it comes to conveying the importance of security to their clients.

This lends itself to brute force vulnerabilities. To be clear though, the issue here is not software in these cases. It’s a people thing. You see, when we talk about brute forcing we’re talking about exploiting a websites access control mechanism (in most cases). When we say access control, we’re referring to the website entry-point (e.g., WordPress – wp-admin / wp-login.php and Joomla – /administrator).

For those that are not technical, imagine walking up to a doorknob and it’s locked. You pull out your awesome key chain, on which you have over 1,000 keys (intense I know), and you proceed to sit there and try every key combination. Yes, highly unrealistic, but what if you could put a robot in your place to go through every combination? Welcome to brute force attacks and the web. Not the smartest, but very easy and proven to be highly effective.

In its simplest form, this is what attackers are doing. They use tools to pass a combination of user and password information to your website’s access control point (think wp-admin / administrator / etc.) hoping they’ll get lucky and get access to your website.

Why Brute Force a Website?

As we mentioned before, the intent of Brute Force attacks is fundamentally different from DoS/DDoS attacks. Their primary objective is access.

In the underbelly of the web, access is king. With it, attackers are able to achieve notoriety amongst their peers, achieve huge economical gains and, of course, bring about unjust pain to your virtual presence.

In most instances, the Brute Force attacks are not manual, instead they are being randomly executed by supporting bots, part of larger networks. These bots are configured to randomly crawl the web for preset conditions (i.e. look for URLs that end with wp-admin). Once the condition is found, the attack is unleashed, and in many instances it’s not too far off target to think that the attacker doesn’t even know who they are attacking, that is until the scan responds with a message declaring the bot found a success. How would your website respond if scanned?

Brute Force Attacks – A Look At the Numbers

It’s always easier when we have statistics to work with, so let’s stick with WordPress and dive into the last 30 days to see what we can come up with.

We went back 30 days and pulled a list of the Top 40 usernames and passwords being used by attackers on WordPress sites specifically. Over that period we were averaging approximately 15,400 brute force per minute. At its peak we were blocking close to 89,400 per minute.

Note: When someone uses the word attack it can be very ambiguous. To help clarify, when we say it in relation to Brute Force and access, we’re referring to attempts against the access point – i.e., wp-admin, wp-login.php, etc…

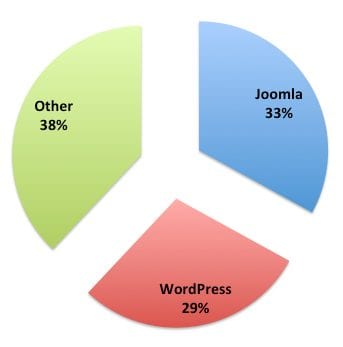

WordPress currently makes up only 29% of our existing Website Firewall network. The chart below provides a better breakdown of the various platforms in our network.

The following images are going to share some specific insights into what we’re seeing. It will provide you a list of commonly used usernames and passwords by attackers. This is important because the attackers do what is most lucrative, in other words showing what is most effective in terms of success rate.

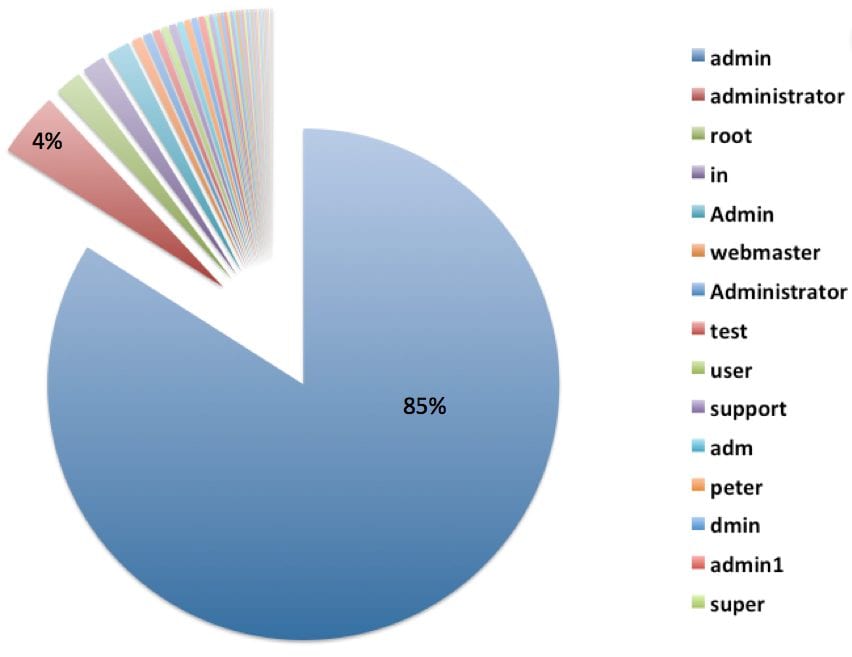

Brute Force – Username Percentage

This pie chart will provide you a complete list of the top 40 usernames attempted during that period, and their percentage dominance. Here are the top 3:

- admin – 84%

- administrator – 4%

- root – 4%

This pie chart shows how overwhelming the percentage is of attacks that use “admin” or “administrator” as the username. Notice the capitalization – it matters.

You likely noticed how lopsided the username percentages appear. Why is admin at 84%? Yes, it’s likely this is tightly attributed to its success rate. The flip side to that argument is it’s the most convenient and easiest to apply. Although tools exist which allow an attacker to rotate various username and password combinations, technological limitations do preclude this from happening and as such, unlike local Brute Force attempts, the attackers must be more pragmatic in their tests. This would lead you to believe that the real emphasis comes in passwords.

It’s about low-hanging fruit.

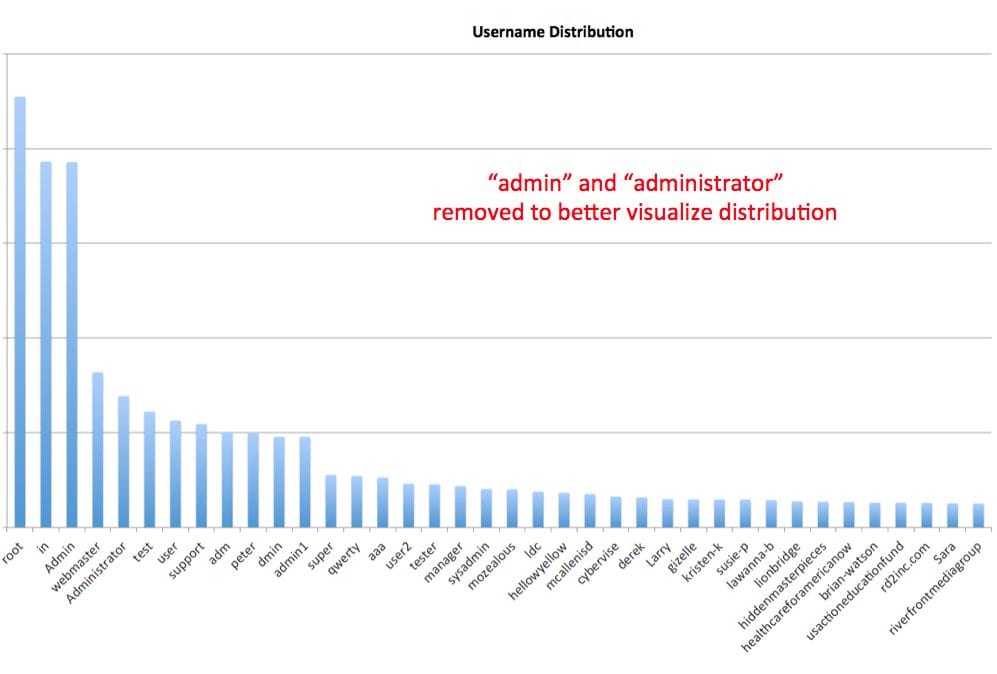

Brute Force – Username Usage Distribution

This table will show you a better illustration of the other usernames being tested, their relationship to the two main culprits, “admin” and “administrator” that we had to remove from the chart to better illustrate the distribution.

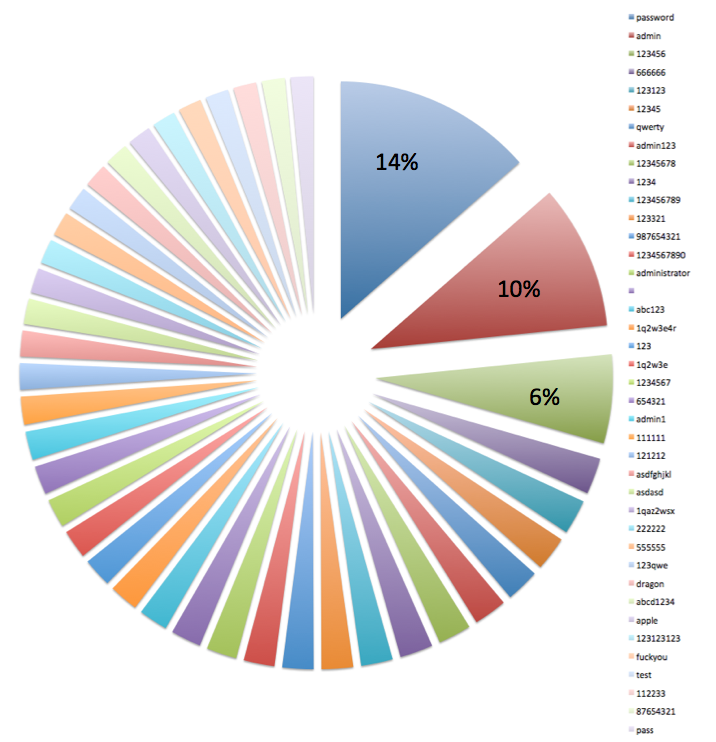

Brute Force – Password Percentage

This pie chart will provide you a complete list of the top 40 passwords attempted during the same period. No surprise to anyone, the top 3 were:

- password – 14%

- admin – 10%

- 123456 – 6%

Technological Advancements

Advancements in technology have made what some thought to be impossible or unrealistic a few years ago into very stark realities today. We no longer have the challenges we did 10 years ago (or even 5 years ago) around networks and latency. Today with the explosion of websites, and massive lack of understanding on the principles of running a website, or server, we have created a pool of blood and the sharks are hungry!

This is facilitated by a plethora of hacking toolkits, easily accessible in the darkest and not so dark corners of the web. These tools allow attackers to easily and effectively perform DoS/DDoS attacks and brute force attacks. While the two types of attacks are fundamentally different, they do share common traits.

The most common trait being the use of compromised environments – both local desktops and web servers. Whether a DoS/DDoS or Brute Force attack, you can rest assured that the odds the attack is coming from a (what should be) clean environment, is very high. Unfortunately, this is a very grave concern, as attacks increase, so do their success rates, and one of their more effective tools continue to be Brute Force for access and DOS / DDoS for service disruption. In either case, scripts are loaded onto servers, existing resources are leveraged and abused, and the end-result is the same – websites are blacklisted, server IP’s blocked, and website owners, like you, have very miserable days, weeks, or months.

The other harsh reality of Brute Force attacks is that they can be synonymous with DOS / DDoS attacks. Although the intent is different, with a brute force attack they are after access, disruption is often a very close and an acceptable second. The DOS byproduct of a Brute Force attack is being facilitated by overloaded shared servers, a majority of what you see on today’s websites, and mismanaged web servers that are too small for the traffic they do receive, let alone unexpected surges.

When you ask a website owner, “Which would you prefer, DDoS or brute force attacks?” – the response is often the same: neither. The problem is, as mentioned above, it’s about scale. Most of you reading this post are not Fortune 100 / 500 companies with large data centers and Network and Security Operation Centers (NOC/SOC).

The question should not be why me? Instead, let’s focus on how to keep yourself protected…

Protecting Yourself From Brute Force / Denial of Service Attacks

Industries are funny and predictable, and the website security space is no different. In comparison to its brother, the desktop. It’s an infant, perhaps in its toddler years. What this means is an explosion of services, each adapting to the latest trends reported by organizations like ours. This growth unfortunately causes a great deal of confusion and information overload for many website owners.

The biggest misconception is this idea that local solutions will address or fix the growing dilemma of DoS/DDoS and brute force attacks. Solutions like plugins and extensions don’t begin to scratch the surface. Just like service providers are jumping on board to build and release solutions, so are the attackers. The problem is either growing at a much faster rate than planned, or maybe it’s just becoming more visible.

In the upcoming years, we’ll discover that true success lies in service-based Website Firewalls with their own infrastructures designed to handle these issues. The real solution comes down to the distribution, segmentation, and analysis of the traffic load.

The biggest problem local solutions face, is just that they’re local. Their limitations are always tied to their local environment, specifically its resources. This puts most website owners at a disadvantage when you think of resources. Remember the discussion above on scaling and the use of compromised environments?

The other challenge is intelligence, not human intelligence, but attack and data intelligence. Local solutions are restricted to their immediate field of vision, unless you’re a CNN, Times, etc. The odds of seeing enough information to make and employ appropriate countermeasures is not in your favor – this is the harsh reality of the situation.

16 comments

Good post, Tony.

I would draw a subtle distinction in your descriptions of DoS and DDoS. A DoS is not a baby DDoS. A DDoS is a very special type of attack because it is just that — distributed. It uses multiple vectors/origins of attack (usually through a network of compromised computers/servers, a botnet) to launch an inordinate amount of traffic at a small set of targets thereby overwhelming the system and/or the bandwidth pipe in and out of the system. This in turn makes the system unavailable for legitimate users. They are, in essence, denied service because of a distributed attack.

Thinking in terms of Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability (CIA), denial of service, whether it’s distributed or not, attacks the availability portion. Mainly this is because it’s restricting access to a resource by making it unavailable.

Brute force attacks attack the confidentiality of a system in that an unauthorized user will gain access to a system that contains confidential data.

A brute force attack, because it can be resource intensive or the system may not know how to handle that number of requests because of database calls or whatever, may result in a denial of service (DoS) but the attack in and of itself is not a true DoS. It just so happens that the outcome of the brute force attack resulted in a denial of service condition for the app at hand.

So while there are any multitude of ways a DoS can happen on a system, there are very specific ways a DDoS can happen. AND they can attack your system in different ways. For example, a DDoS could attack the network layer of the data center or host itself overwhelming the infrastructure to your server OR it could be an application level DDoS where a series of specially crafted calls unique to the application you are running ties up the system in a way that legitimate users cannot access it.

For me, one of the key differences is intent. While it is possible that you could be collateral damage in a DDoS situation (your server is located in the same data center as the true target), it is usually the case that someone is launching a DDoS at you to prove a point or make a statement. Think hacktivism. Someone launching a brute force attack on your system is after sensitive data or access to use at a later time in a more strategic way like making it a part of a botnet to attack other systems.

I read somewhere once, can’t remember where, that hacktivist groups like Lulz or Anon usually resort to DDoS to make their point when other avenues of attacks fail. Because it’s easy and cheap and still makes noise.

For small businesses this is important to remember as they can be victims of automated scans/attacks. Oftentimes, the best approach is one of multiplicity — like layers of an onion. “Defense in depth” is what the folks call it, I think. The more layers they have for attackers to deal with, the harder it is for attackers to make an impact. As you say in your post, they go for the low hanging fruit. If you make it hard for them, automated systems and the lazy script kiddie will have a tough time making inroads to your system.

Hey @rubicant3:disqus

Yes, correct on all accounts. My intent in the post was an explanation at a level that all website owners would be able to read and understand, it’s why things were explained the way they were. Regardless, thanks for the input and thoughtful response.

Lastly, you’re correct, the key differentiator is in definitely intent.. 🙂

All the best,

Tony

Absolutely — I think that’s a great approach, especially since you’re drawing a distinction between DDoS and brute force attacks. As a sys admin and web guy, I just wanted to go a layer deeper for the more technically inclined. Can’t help it, I guess. 😉

Like I said, great post still — would be awesome to do a series of posts for the budding website owner on basic security concepts. You could do like a “Website Security 101” email drip campaign or something.

Hey

I don’t mind at all.. :).. just shows me you read it, and if it encourages discussion and sharing of thoughts then it did what it was meant to do. Love the feedback.

I do love your idea though..

Tony

Brute force attacks rely on trying thousands of passwords so rate-limiting some critical URL’s could be handy.

Modules like Nginx’s limit_req_zone who in fact drop requests when going over a threshold could be wiser rather than leave to PHP to evaluate and act against those attacks.

Great post. Really pretty graphs! I experienced a brute force attack on my WP site last year and wrote about my experience and how I tried to fix it and then finally DID fix it. http://webeminence.com/brute-force-wordpress-login

I agree the plugins are not a solution but they can provide some useful info and defense as I mention in my post. You can read my post to find out what was the secret weapon and has worked thus far. Many people seem to overlook it.

Now reading your post, I’m also wondering if moving wp-admin might be a good solution. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen that recommended.

This is great! I can so share with clients! Thank you

Hi @KarmicVisions:disqus

That right there was the point, it makes me happy to hear you say that. It’s to serve as an educational piece that can be referenced as needed, especially when trying to convey to clients the differences.

Thanks

Tony

I like Rubicant3’s suggestion on a series of posts for us technically

challenged web site owners on basic security concepts. Until I signed up

for Sucuri services and am now able to see how my site is being probed

for security weaknesses and how many virtual patches Sucuri has

protected my site with, I never realized all this activity was taking

place to the extent that it is. I have been reading the Sucuri blog

posts but have to admit some go right over my head. I search for

explanations but then you never know if what you are reading around the

internet is correct or if you are being misinformed on purpose. The bad guys I have found sometimes try to pose as the good guys giving security advice.

To have a place to ‘go to’ to learn the right security stuff would be

quite a draw for us technically challenged web site owner/operators.

Heck, even setting up a pay to learn section would be great for those of

us that want to better understand and learn about web site security.

And a plus would be better educated web site owners creating more secure

sites making the web a safer place for everyone to roam.

Hi Tony Perez,

Great Post,

Thanks for sharing the useful info DDos 🙂

-Mosam

Recently I wrote about my experiences with these sorts of attacks and what I did about them, including showing how the Sucuri cloud proxy service helped stop an attack. The post is at http://effectivemarketingontheweb.com/what-a-brute-force-attack-on-a-wordpress-website-looks-like-and-what-you-can-do-about-it/.

Hi Dave

Sorry I missed this comment, that’s a really nice write up, thanks for sharing. Be sure to check back, we’ve added a lot of features in the past month that you might find very helpful.

Y’all should check out this beautiful rendering of a Digital Attack Map: http://designandviolence.moma.org/digital-attack-map-google-ideas/

Thanks for this. I understood a lot of it (layman here). Question: I’m moving my websites to a cloud instead of a server. What additional protections (other than those provided by my cloud provider) should I consider?

Great article, and well written, thanks Tony.

Completely agree about local solutions not always being applicable. Take, for example, a brute force attack against a WordPress site (e.g. http://yourdomainname/wp-admin). Repeated tries at breaking the security will generate a significant resource load on the server (possibly creating a sort of DoS of it’s own in the process), as WordPress executes a bunch of files every time. A web firewall makes so much more sense as it stops suspicious traffic much earlier in the cycle. I use Cloudflare for a few of my sites, but I do find it can be over-zealous at protecting my site – even I’m locked out sometimes, and using an IP address that has been whitelisted at Cloudflare. Would consider the Sucuri WAF, but still keen to keep other Cloudflare benefits (which presents a bit of a cost issue).

Great article. Can you explain to us non-techies how we could change our entry page from being wp – admin? If that’s what the bots are looking for, wouldn’t using a different URL prevent most of the attacks?

Comments are closed.